There are few more entertaining sports when played at this level, argues JAMES NALTON

JOHN WIGHT writes on the famous final battle between Ali and Frazier, and the latter’s brilliant trainer Eddie Futch

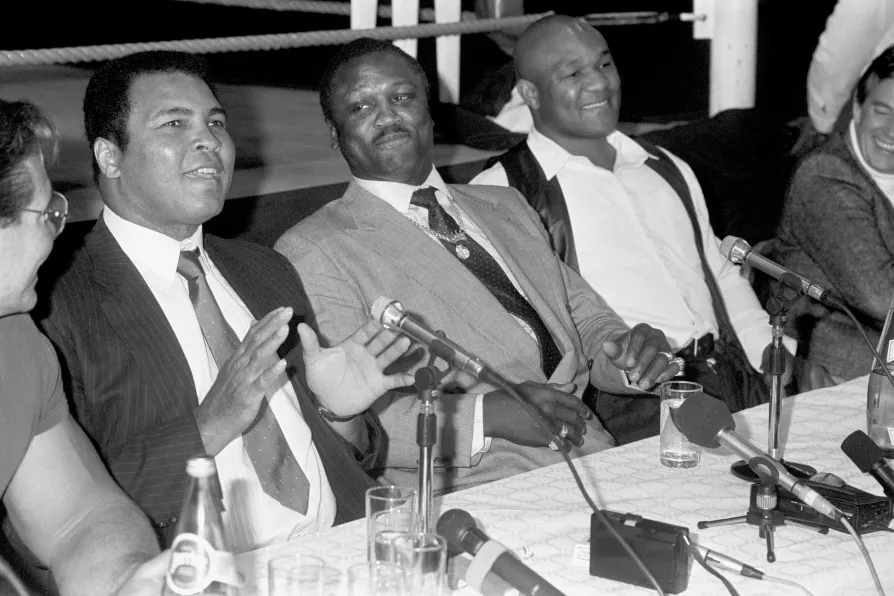

(L-R) Former World Heavyweight Champions Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier and George Foreman at a press conference to publicize the launch of the video 'Champions Forever', October 17, 1989

(L-R) Former World Heavyweight Champions Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier and George Foreman at a press conference to publicize the launch of the video 'Champions Forever', October 17, 1989

“SIT DOWN, son. It’s all over. No-one will forget what you did here today.”

The aforementioned words, spoken by trainer Eddie Futch to Joe Frazier at the end of the 14th and penultimate round of arguably the most punishing heavyweight fight ever fought — between Frazier and his arch-nemesis Muhammad Ali in Manila on October 1 1975 — have justifiably gone down in boxing folklore. They resonate still today as the most powerful example of a trainer saving a fighter from himself.

The sheer courage displayed by Futch in pulling his fighter out of the fight at such a late stage was only matched by the courage displayed by Frazier in the final bout of the last fight in the trilogy he fought with Ali.

Theirs was a bond forged in blood, involving two black heavyweights who by the end of their long rivalry were more interested in being champion of one another than they were of the world, it was so bitter and hard fought.

As Ali said of their rivalry after finally retiring from the ring: “I’m sorry Joe Frazier is mad at me. I’m sorry I hurt him. Joe Frazier is a good man. I couldn’t have done what I did without him, and couldn’t have done what he did without me.”

Ali was here referring to the merciless insults he levelled at Frazier in the lead-up to the fight, repeatedly calling him an Uncle Tom, ignorant — even going so far as to produce a toy gorilla at the pre-fight press conference, punching it while calling it “Joe.”

The Thrilla in Manila, as this epic fight is famously known, saw two men who, in clear physical decline, do battle in the Phillipine capital. Remarkable to contemplate that Ali had already fought three times that year prior to facing Frazier in the sweltering heat.

By now, money problems dictated that he fight as often as possible in what was a losing battle against Mother Nature. As for Frazier, he had fought just once prior to Manila — this against Ali’s close friend and longtime sparring partner, Jimmy Ellis.

Returning to Eddie Futch; it was he who is credited with developing Frazier’s bobbing and weaving style, using his relatively small stature as a heavyweight to his advantage by coming in low to force his larger opponents to punch down and thus lose a significant portion of their power. In so doing, he turned Frazier into the “Smokin’ Joe” legend he became.

Against Ali in the first fight with Frazier at Madison Square Garden on March 8 1971, known to history as the Fight of the Century, Futch devised the game plan that would clinch Frazier victory by unanimous decision to retain his world title.

Futch had taken note that Ali leaned back to avoid incoming punches to the head, and that he also threw a technically deficient and loose right uppercut that left an opening that Frazier could exploit with his notorious left hook.

Futch advised Frazier to concentrate on breaking up Ali’s body until the late rounds to make him lose mobility, then to start firing the left hook over the top of Ali’s low right hand. Frazier did precisely that, and ended up dropping Ali with a vicious left hook to the chin in the very last round of what had been a 15-round all-action back-and-forth affair.

The second fight, and least remarked upon, of their legendary trilogy unfolded on January 28 1974, again in New York at Madison Square Garden. This turned out to be an ugly affair, with Ali more holding than fighting throughout, continually pushing Frazier’s head down when he came inside to unload, and earn himself a regular chorus of boos from the crowd. That Ali won a narrow unanimous decision on points would have come as small comfort in the end.

The Philippines in 1975 was ruled by the dictator Ferdinand Marcos. When he wasn’t having his opponents tortured and murdered, Marcos was siphoning off the country’s wealth into a variety of Swiss bank accounts.

Not that promoter Don King would have been minded to complain. On the contrary, this former street thug and numbers runner from Portland was more than comfortable doing business with such dictators. For him, the dollar talked and all else walked.

Of everything written on the Thrilla in Manila, author Mark Kram’s book, Ghosts of Manila, remains the definitive work. Here he describes Ali at the official dinner, hosted by Marcos, after the fight:

“Ali had never before appeared so vulnerable and fragile, so pitiably unmajestic, so far from the universe he claims as his alone. He could barely hold his fork, and he lifted the food slowly up to his bottom lip, which had been scraped pink.

“The skin on his face was dull and blotched, his eyes drained of that familiar childlike wonder. His right eye was a deep purple, beginning to close, a dark blind being drawn against a harsh light. He chewed his food painfully…”

Ali’s epic battle with the thunderous George Foreman in Zaire (now Democratic Republic of the Congo) in 1974 had already earned him a place in the stars. In overcoming Frazier in Manila a year later, he entered the pantheon of greatness reserved for those willing to sacrifice themselves for the kind of glory that will live on after they are gone.

Frazier died on November 7 2011 in Philadelphia. He was 67 years old, and at the time of his death he was living above his gym, located in an unfashionable part of town on North Broad Street. A visibly shaking, Parkinson’s stricken Ali attended the funeral.

One can only speculate as to the mixed emotions he experienced, standing there paying tribute to his once nemesis and more than worthy ring adversary.

When Ali himself died in on June 3 2016, at age 74, the man gave way to the legend. Returning to Mark Kram and Manila: “Time may well erode that long morning of drama in Manila, but for anyone who was there those faces will return again and again to evoke what it was like when two of the greatest heavyweights of any era met for a third time, and left millions limp around the world.

“Muhammad Ali caught the way it was: ‘It was like death. Closest thing to dyin’ that I know of’.”