SIMON PARSONS is charmed by a hilarious tender show that will open the eyes to the delights and possibilities of puppetry

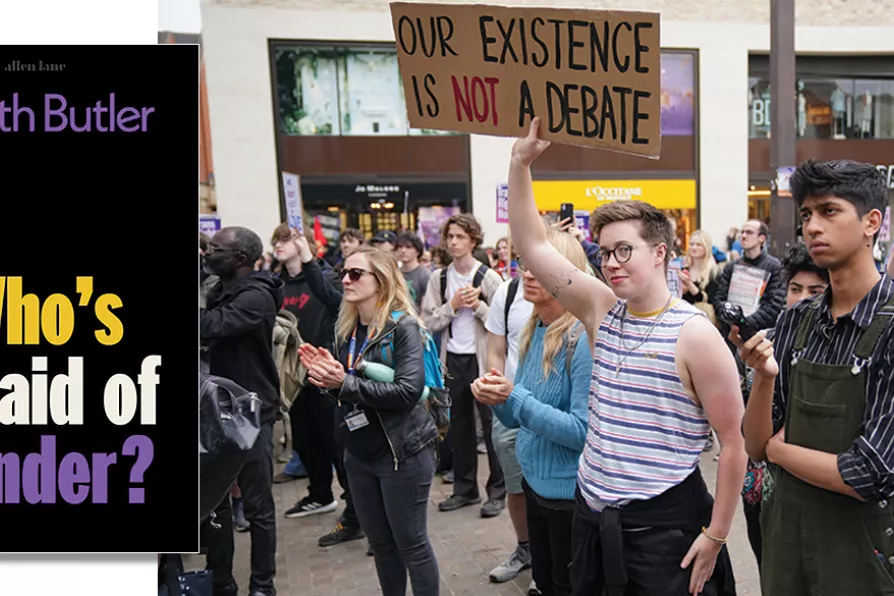

OPPOSITES COLLIDE: Protest in Oxford where Professor Kathleen Stock is due to speak at the the Oxford Union, May 30 2023

OPPOSITES COLLIDE: Protest in Oxford where Professor Kathleen Stock is due to speak at the the Oxford Union, May 30 2023

Who’s Afraid of Gender

Judith Butler

Allen Lane, £25

ANYONE dipping even the most tentative toe into the currently tempestuous waters of gender discourse won’t be able to venture too far without encountering the name Judith Butler.

Works like Gender Trouble and Bodies That Matter have become key texts in global gender studies, even as many of their theories have been misinterpreted, or just plain misunderstood over the years. That being so, it’s useful that rather than taking another deep dive into the intricacies of gender-oriented cultural philosophy, this book instead confronts head-on the current and heated so-called culture war that has sprung up in public discourse around gender.

Butler has a not wholly undeserved reputation for writing in dense academese but they’ve thankfully reined in that tendency for the most part here to produce a largely reader-friendly text.

WILL PODMORE welcomes the case put by a feminist, disentangling the abusive rhetoric of the trans rights debate

CAILEAN MCBRIDE welcomes a refreshing and timely study of the way officialdom creates structures that exclude LGBT+ rights and humanity