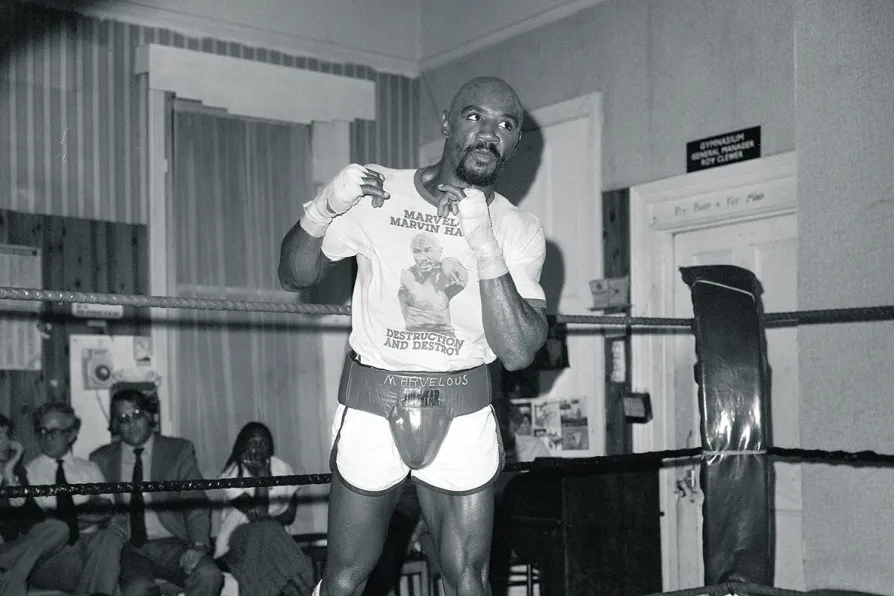

Marvin Hagler

Marvin Hagler

“EIGHT Minutes of Fury” is the title of American sportswriter Pat Putnam’s peerless account of one of boxing’s all-time classic encounters, involving Tommy “The Hitman” Hearns and Marvelous Marvin Hagler in what remains the greatest three rounds of boxing there’s ever been — and likely ever will be.

The setting was a specially built outdoor arena and ring erected on the tennis courts of Caesars Palace hotel and casino in Las Vegas, the date was April 15 1985, and watching the fight back today still renders you stunned at the ferocity unleashed by two of the sport’s all-time greats, crashing into one another like men who were bent on taking possession of the other’s heart.

Hearns at 26 was the young pretender looking to seize from Hagler’s head the undisputed middleweight crown, which Hagler himself had torn from the head of Britain’s Alan Minter five years previously at London’s Wembley Arena.

In recently published book Baddest Man, Mark Kriegel revisits the Faustian pact at the heart of Mike Tyson’s rise and the emotional fallout that followed, writes JOHN WIGHT

As we mark the anniversaries of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, JOHN WIGHT reflects on the enormity of the US decision to drop the atom bombs

From humble beginnings to becoming the undisputed super lightweight champion of the world, Josh Taylor’s career was marked by fire, ferocity, and national pride, writes JOHN WIGHT

Mary Kom’s fists made history in the boxing world. Malak Mesleh’s never got the chance. One story ends in glory, the other in grief — but both highlight the defiance of women who dare to fight, writes JOHN WIGHT