Amid riots, strikes and Thatcher’s Britain, Frank Bruno fought not just for boxing glory, but for a nation desperate for heroes, writes JOHN WIGHT

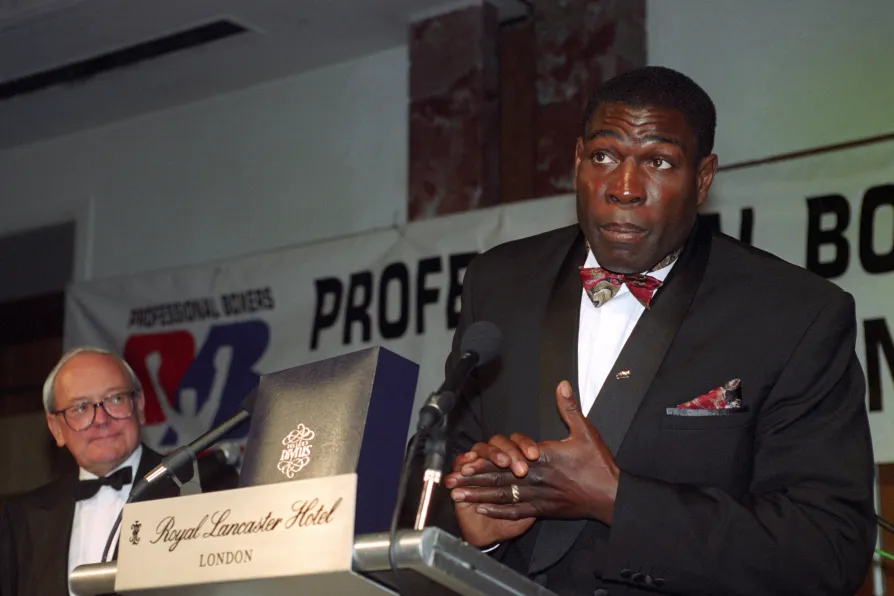

British Heavyweight boxer Frank Bruno speaking at the first ever Annual Dinner of the Professional Boxers Association in London, watched by commentator Harry Carptenter, June 22, 1994

British Heavyweight boxer Frank Bruno speaking at the first ever Annual Dinner of the Professional Boxers Association in London, watched by commentator Harry Carptenter, June 22, 1994

FRANK BRUNO was part of the sporting and cultural furniture in Britain throughout the 1980s. With his colourful made-to-measure suits and deep belly laugh, he was affable to the point of parody at times. Yet he lit up British boxing at a time when the mere thought of there ever being a British heavyweight world champion was such an alien concept that the possibility had long been scorned.

Bruno provided hope at a time when hope was in short supply, and no wonder. Thatcher and her extreme free-market economic and ideological creed, which came to be known as Thatcherism, turned British society on its head. The days of a secure job for life were set on fire in the name of private capital. Whereas previously, since the end of the second world war, the role of the economy had been viewed as that of serving the needs of society, by the end of the 1980s society had been consigned to the role of serving the needs of the economy.

In 1980, the trade union movement was a key pillar of social stability in Britain. By 1989, its power had been greatly diminished. Thatcher had unleashed war on a movement whose weakness she and hers well knew was sectionalism. The result was one after the other of the country’s major industries being decimated to the point of the country’s industrial base being destroyed in the name of the new religion.

In 1980 a pint of lager set you back 40p. By 1989 you were looking at paying on average 99p for the same privilege. In music, movies and television, the changes were as rapid as they were bewildering. The City of London’s financial services sector was anointed as a temple of economic growth, and its deregulation in the name of unfettered greed changed everything.

The Falklands war in 1982, the Irish hunger strikes in 1981, the miners’ strike between 1984 and 1985, the Brighton bomb of 1984, Live Aid in 1985 at Wembley, the Toxteth and Brixton riots of 1981, the Iranian embassy siege and subsequent SAS rescue mission, again in 1981 — each of the aforementioned were among the epic events that both fractured and defined British society during this tumultuous and tempestuous decade.

Frank Bruno, at age 20, made his professional debut on March 17 1982 against Mexican journeyman Luis Guerra. The location was the Royal Albert Hall in London, and Bruno’s appearance on the bill was eagerly awaited. As an amateur the big Londoner with the physique of a Mr Universe contender had won the British heavyweight ABA title in convincing fashion two years previously.

It was an achievement that brought him to the attention of veteran trainer Terry Lawless and promoter and Lawless’s business partner and likewise veteran of the game, Mickey Duff. They both saw in Bruno the potential for boxing stardom, and they were right. What Bruno lacked in speed and footwork, he made up for with the kind of clubbing punches that quickly saw him become a fan-favourite. Add to the mix the rapport he established with the BBC’s Harry Carpenter at ringside, and the stage was set for the brand of celebrity not enjoyed by a British heavyweight since the days of Henry Cooper.

From that March evening at the Royal Albert Hall, Bruno enjoyed a run of 21 victories from 21 contests, all by way of KO or TKO. By 1984, when he faced the formidable American James “Bonecrusher” Smith in front of a sold out Wembley Arena, a man who began boxing at a boarding school for problem kids in Sussex, he could do no wrong.

The fight was a non-title 10-rounder. It was by far the hardest test of Bruno’s professional career to date. Smith was supposed to lose but had come to win, and came out swinging from the off. What ensued was a brawl between two giants who each took as much as they dished out. By the last round Bruno was out on his feet while Smith did what veterans do and went to the well one last time to get the knockout.

By now Terry Lawless and Mickey Duff were in no doubt that Bruno had to be carefully matched, so as to protect him from his own limitations and also to protect their investment. A winning streak made up of seven wins followed, before Bruno entered the ring at Wembley Stadium in front of 40,000 fans to face Tim Witherspoon. Up for grabs was the American’s WBA title. It was billed as a 12-round fight but ended in the 11th, when Bruno was rocked by a huge right hand that dropped him to the canvas. Lawless had seen enough by then and threw in the towel, wisely saving his fighter from taking undue punishment much to the irritation of many in the crowd.

1989 was the year when the Berlin Wall came down, 96 Liverpool fans lost their lives at Hillsborough, and which marked Thatcher’s tenth year in Downing Street. It was also the year in which Frank Bruno faced Iron Mike Tyson for the first time.

Those of a certain age will recall the excitement that gripped the nation over the prospect of “our Frank” facing the cartoon villain that was Tyson in Vegas. In the lead-up, Carpenter outdid himself in setting the stage. We were introduced to Bruno’s wife and young children as every drop of sentimentality was wrung out in the cause of humanising Bruno and dehumanising Tyson. The result was the fight being turned into a battle between good and evil. Bringing the dragon of Mike Tyson to heel was now a sacred cause to be undertaken in the name not only of boxing but civilisation itself, such was the fear this young wrecking ball of a heavyweight struck in the hearts and minds.

As to the fight itself, Bruno tried to fight fire with fire, but the fire he faced that night was just too ferocious to be put out. Five rounds is what it took before Tyson succeeded in breaking through the last line of Bruno’s defences to catch him with two vicious uppercuts while he was up against the ropes. It prompted referee Richard Steele to step in and bring matters to a halt.

Frank Bruno’s assigned role as matador to Mike Tyson’s bull had ended in defeat. It marked a cruel end to a cruel decade.