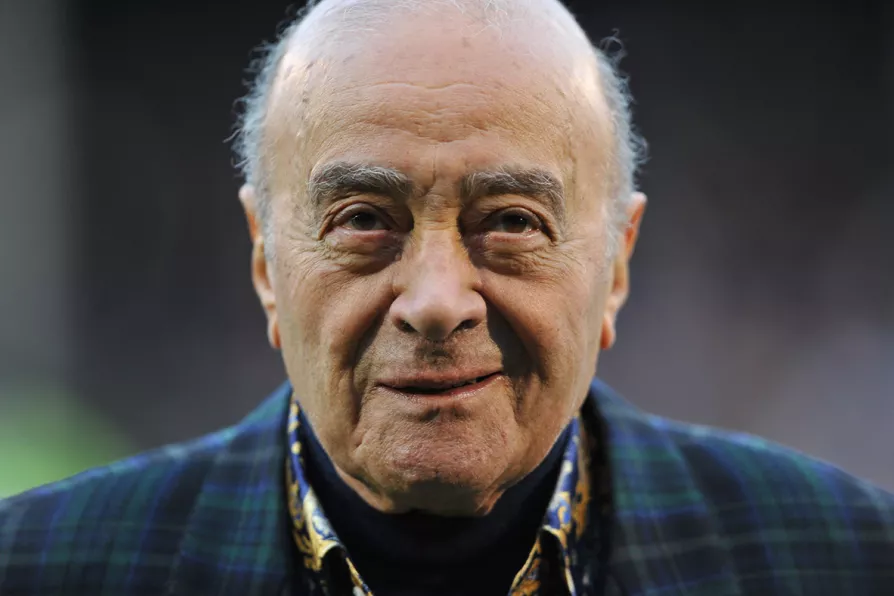

Mohammed Al Fayed, January 12, 2013

Mohammed Al Fayed, January 12, 2013

WHERE the Metropolitan Police appear to be taking allegations made against the former Harrods boss, Mohamed al-Fayed seriously, the latest statement by Harrods boss Michael Ward bears close analysis.

It is unusual in that it breaks with the mystifying nature of most corporate speech, ditches the passive case and states unequivocally that the previous owner, al-Fayed, “presided over a toxic culture of secrecy, intimidation, fear of repercussion and sexual misconduct.”

The revelations that more than 20 former Harrods workers say the billionaire boss sexually assaulted or raped them has knocked the shine off al-Fayed’s benign image that the TV series The Queen has so misleadingly fostered.

Al-Fayed, who two years ago departed this life at ripe old age of 94, bought Harrods in 1985 and sold it in 2010.

The new owner is the immensely well-endowed sovereign wealth fund of Qatar, Britain’s imperial satrap on the north-east coast of the Saudi petro-monarchy with a human rights and women’s equality set-up that bears examination only in comparison with its bigger neighbour.

The presumption is that Ward has been give wide authority to deal with the claims arising from al-Fayed’s conduct. Credit where credit is due.

Ward says: “We have all seen the survivors bravely speak about the terrible abuse they suffered at the hands of Harrods former owner Mohamed Fayed.”

He then went on to restate: “…we failed our colleagues and for that we are deeply sorry.”

While we are parsing the language deployed around this issue, let’s look at this term, “colleagues.”

When inserted into the dominant narrative around workplace relations, the term functions to obscure the precise character of the unequal disposition of power, and its use in this context exposes just how inadequate corporate-speak is in revealing the truth about the situation in which these young women found themselves during the al-Fayed era.

The firm is facing legal action for a huge range of issues — negligence and assault, rape, serious physical and long-term psychological injury.

Lawyers acting for the women say: “…for decades the most prestigious department store in the country effectively became a vehicle for human trafficking by Mohamed al-Fayed.”

What made al-Fayed a monster was not just the power he exercised as an employer, but also the power he exercised as a man in the existing system.

This was not simply the ability he possessed to deprive these young women of their livelihood. It also arose from the enormous social power he exercised; to assault them, to compel their consent to intrusive examinations that violated both their bodies and their dignity; and to command various functionaries and medical specialists to coerce them.

To this was his power to command their silence. Simplistic analyses which locate women’s oppression simply in either the power exercised by employers or of men are not adequate to deal with this particular manifestation of power.

It is the realm of ideology — a key site for the construction and reproduction of women’s oppression — that cannot be dissociated from economic realities that appear most transparently in the relations between workers and employers and less transparently in the way society is organised and ideas disseminated.

Al-Fayed’s interpersonal power existed in interdependency with established structures of sex and class inequality. Capitalism’s structures of inequality appear as ideological to legitimate the interpersonal power of rich and privileged men in relation to both working-class men and women in general.

That al-Fayed’s victims are beginning to come forward is a testament to their courage and determination, but also the ways in which the enormous power — rooted in the dominant ideology and in the structures that support it — is beginning to dissolve.