PETE HIRST introduces a theatre company from Wakefield dedicated to the propagation of socialist perspectives on present British political realities

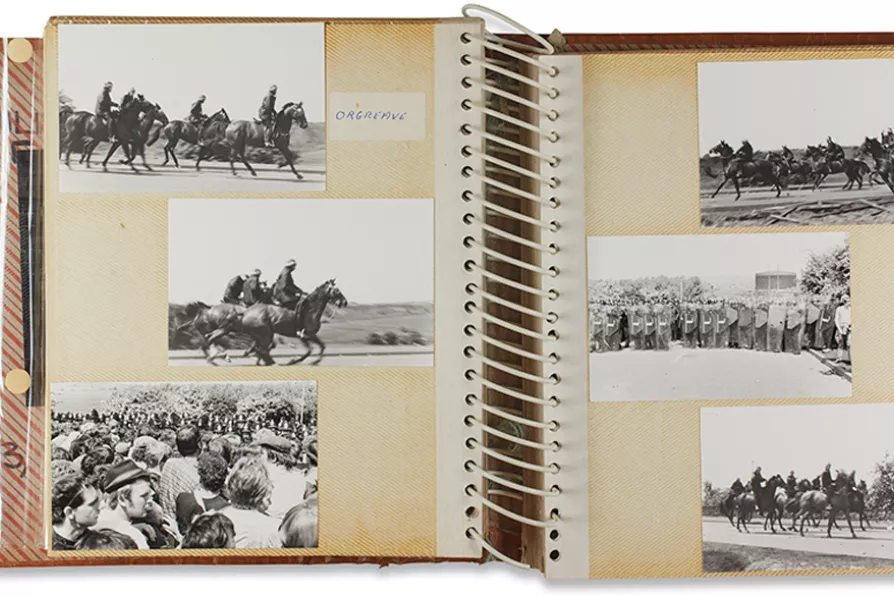

Spread from photo album 12 March 1984. Photo: Philip Winnard

Spread from photo album 12 March 1984. Photo: Philip Winnard

THIS exhibition displays photographs made during the Miners’ strike and looks at how they were used and disseminated through the visual media of the time.

One side used images to illustrate chaos on picket lines being sprung by a so-called “enemy within,” while those in support of the strike attempted to debase such media bias, by showing the violence acted out by the state in police brutality, as well as the cruelty of the economic destitution endured.

Photojournalists John Harris and John Sturrock showed the day-to-day activities such as union meetings, winter picket lines, and coal riddling. Both photographers’ images were used by left-wing and union press, as they made careful decisions around who to licence to, knowing well the fractious mediatic landscape and its potential pitfalls.