DENNIS BROE finds much to praise in the new South African Netflix series, but wonders why it feels forced to sell out its heroine

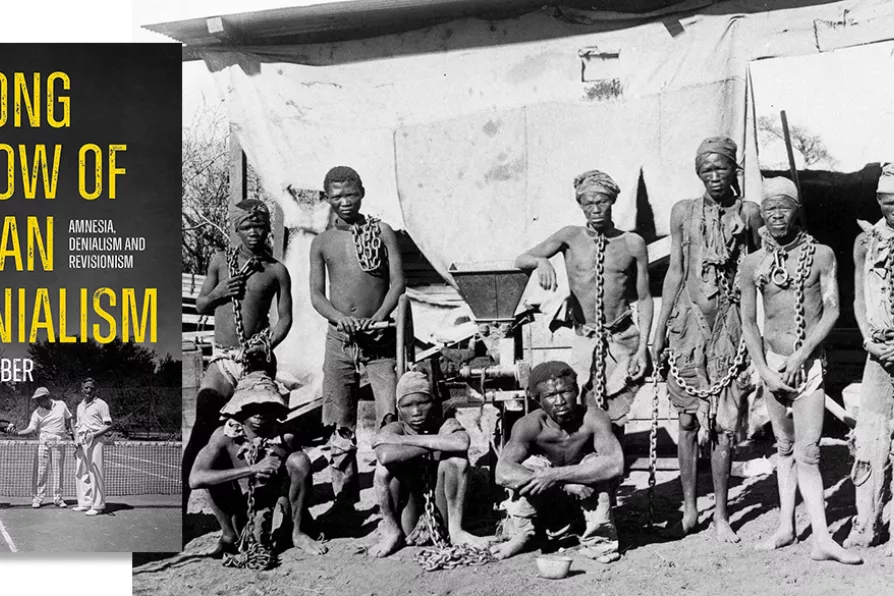

Chained Herero and Nama prisoners during the campaign of ethnic extermination and collective punishment waged against the Herero (Ovaherero) and the Nama in German South West Africa (now Namibia) by the German Empire, between 1904 and 1908. Between 65,000 and 100,000 Africans were killed, approx 80% of the indigenous population

[Public Domain]

Chained Herero and Nama prisoners during the campaign of ethnic extermination and collective punishment waged against the Herero (Ovaherero) and the Nama in German South West Africa (now Namibia) by the German Empire, between 1904 and 1908. Between 65,000 and 100,000 Africans were killed, approx 80% of the indigenous population

[Public Domain] The Long Shadow of German Colonialism - Amnesia, Denialism and Revisionism

Henning Melber, Hurst, £30

HENNING MELBER moved to Namibia (former South West Africa) with his family of German immigrants, in 1967. He joined the South West Africa Peoples’ Organisation in 1974 remaining an anti-colonialism activist ever since.

Germany’s colonial period was short compared to those of its European neighbours, lasting from 1884 until 1914. Following defeat in WWI, Germany’s African colonies, South West Africa (Namibia), Cameroon, Togoland (Togolese Republic and Ghana), German East Africa (Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi) and those in the Pacific, the Mariana, Marshall and Caroline Islands were distributed among the victor nations.

German companies continued to operate in these territories, often coming into conflict with those of the victors.

MOLLY DHLAMINI welcomes a Pan-Africanist and Marxist manifesto that charts a path for Africa’s resurgence