STEPHANIE DENNISON and ALFREDO LUIZ DE OLIVEIRA SUPPIA explain the political context of The Secret Agent, a gripping thriller that reminds us why academic freedom needs protecting

KENNY MACASKILL delivers his assessment of Nicloa Sturgeon’s account of her political career

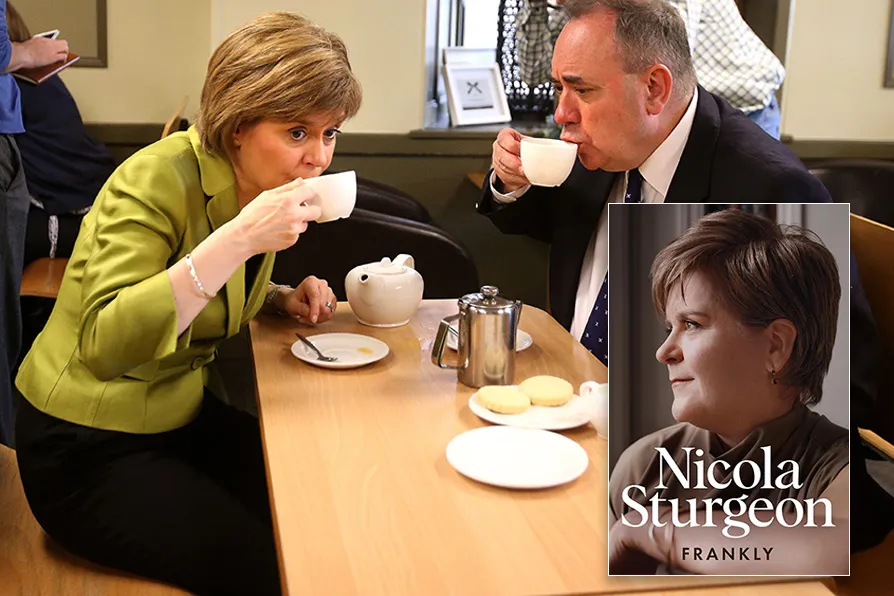

STORMS AND TEACUPS: Nicola Sturgeon and Alex Salmond on the General Election campaign, 2015

STORMS AND TEACUPS: Nicola Sturgeon and Alex Salmond on the General Election campaign, 2015

Frankly: The Revelatory Memoir from Scotland’s First Female and Longest-Serving First Minister

Nicola Sturgeon, Macmillan, £14

I’VE known Nicola Sturgeon for nearly 35 years, yet never really knew her. I’m not alone in that but anyone hoping for an insight into the person, never mind a window into recent events, will be sadly disappointed. Although titled “Frankly,” her biography is far from candid, with much of significance downplayed and even more left unsaid.

She’s someone who’s frankly cold with little small talk and the Scottish monicker “Nippy Sweety” is well-deserved. The public ebullience and gladhanding was modelled on Alex Salmond, though while he was spontaneous and genuine, she was a facade and false.

I recall sitting in the back of a government car alongside her as we were early for a funeral service. Neither of us had ministerial papers and it was before social media had arrived. After trying the usual — work, weather, holidays — with no response I simply gave up and looked out the window.

For sure she’s from a humble background, her rise has been meteoric and she’s an outstanding debater with excellent presentation skills. But the book also discloses someone on a mission, and for herself not party or cause. The wording is “I,” “me” and “my party,” never “us,” “we in the SNP,” let alone “the independence movement,” which bloomed in the run-up to the referendum.

To be self-obsessed and self-serving is perhaps only to be expected from someone also dubbed the “Selfie Queen.” While she claims at the outset to be suffering from “imposter syndrome,” it is soon refuted by her own hand when, already on page 17, she is confessing to a “burning ambition” and even possessing a “sense of destiny.”

She claims she was “never entirely comfortable with the Rock Star Mania” which she created, maintained and revelled in. Following her election as leader and first minister, she booked the Glasgow Hydro and other major venues for a tour which was more about promoting her than advancing the cause or improving the country. That irked Alex Salmond as the costs were considerable, with funds that appeared to have been kept back from the referendum campaign to launch her. Hogging the spotlight was to be a hallmark of her leadership.

Peter Murrell, her husband, who was also SNP CEO, remained in position even after she took office and her defence of that is disingenuous. A clear conflict of interest, which even a bowling club wouldn’t countenance, is simply deflected by stating that Salmond had wanted him sacked. All Salmond had said was that he would need to move on within six months, but she was adamant that he remain. Now separated and with Murrell facing serious charges relating to party funds, she’s silent on his actions, but what will come out won’t look good.

Her description of politicians and staff vary from the effusive for those she likes, to the waspish for those with whom she disagrees, or who’ve challenged her. There’s a gratuitous barb at Jeremy Corbyn as displaying “aloofness and sneering superiority.” Knowing Jeremy, “a gentleman and modest” is a more accurate description. But her gushing at meeting Hillary Clinton, and her selfie with Alastair Campbell, perhaps explain her pejorative comments.

She describes David Cameron as lacking the “pursuit of any great cause” (which is probably correct) but other than genuflection towards independence, her tenure and life are equally marked by the absence of any ideology or driving passion. Her demand to be judged on education sees her convicted, and in the book both that and other areas of policy are downplayed. Transgender prisoners in the female estate are dealt with by the bland assertion that she didn’t see women as being endangered. This is gob-smacking given the vulnerability of so many.

Other critical issues are similarly glided over. Covid, along with the transgender issue, will define her. She may have been an excellent communicator, but in reality, much was simply about being “Boris plus or minus” — hardly a high bar. Posing the question “Should we have protected care homes better?” she answers: “It might be Yes.” This is staggering, and of little comfort to the bereaved.

The successful court action by Alex Salmond against her government is described as a “procedural error.” This, despite the fact that it had seen the presiding judge, now head of the Scottish judiciary, describe her government’s actions as “unlawful, unfair and tainted with apparent bias,” and impose punitive expenses.

Though it’s Sturgeon’s autobiography, Salmond looms throughout, with frequent references, ranging from the derisory to the defamatory. Excerpts from the book released by the publishers before copies were even on shelves were firmly rebutted by former ministers and staff. These range from the ludicrous suggestion that Salmond had little knowledge of the white paper which was the prospectus for independence, when he was a master of detail; via the shameful suggestion he had opposed same-sex marriage, when he was socially liberal as well as a social democrat; to the utterly ridiculous suggestion that Salmond may have leaked the story of his looming criminal charges to the press himself, which was swiftly rejected by the journalist involved.

Although she denies that there was a conspiracy against Salmond, it’s clear that he still haunts her and will continue to do so from the grave, as a court case continues and the clamour for a public inquiry grows.

This autobiographical effort won’t turn the tide. It lacks substance and is as evasive as her evidence was to the parliamentary committee on the Salmond case and the Covid Inquiry. History will judge her, and it will be harsh and unforgiving.