JOHN GREEN, MARIA DUARTE and ANGUS REID review Fukushima: A Nuclear Nightmare, Man on the Run, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and Cold Storage

[Pic: Daniel Naczk/CC]

[Pic: Daniel Naczk/CC]

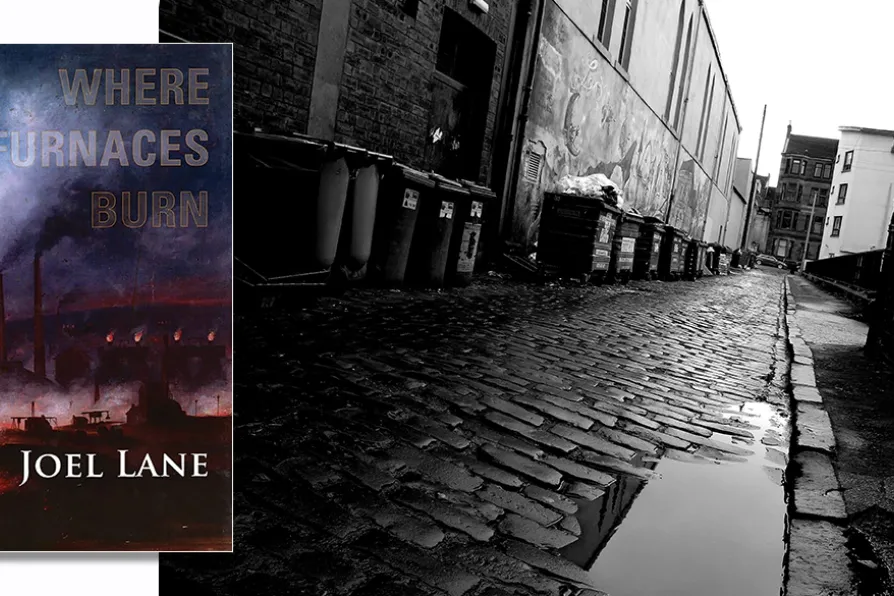

Where Furnaces Burn

Joel Lane

Influx Press, £9.99

JOEL LANE was a dissident mythmaker. In his novels and short stories, he reworked the traditions of supernatural horror and noir crime to confront the cruelties, absurdities and horrors of neoliberalism.

Lane’s unexpected death in 2013, at the age of just 50, silenced a voice of considerable intelligence and imaginative power. Fortunately, Influx Press are publishing new editions of his books. Where Furnaces Burn, the latest to be reissued, is a medley of 26 thematically and stylistically linked short stories, each of them an episode from the 24-year career of a West Midlands Police officer. In the opening story, the narrator is a trainee constable in late 1970s Wolverhampton; at the end of the book, and the close of his career, he is a damaged and disillusioned detective sergeant.

The format is deceptive. The police procedural elements are embarkation points for unsettling, genre-blending expeditions into places neglected by corporations and politicians — West Midlands districts with rotting infrastructure and marginalised people.