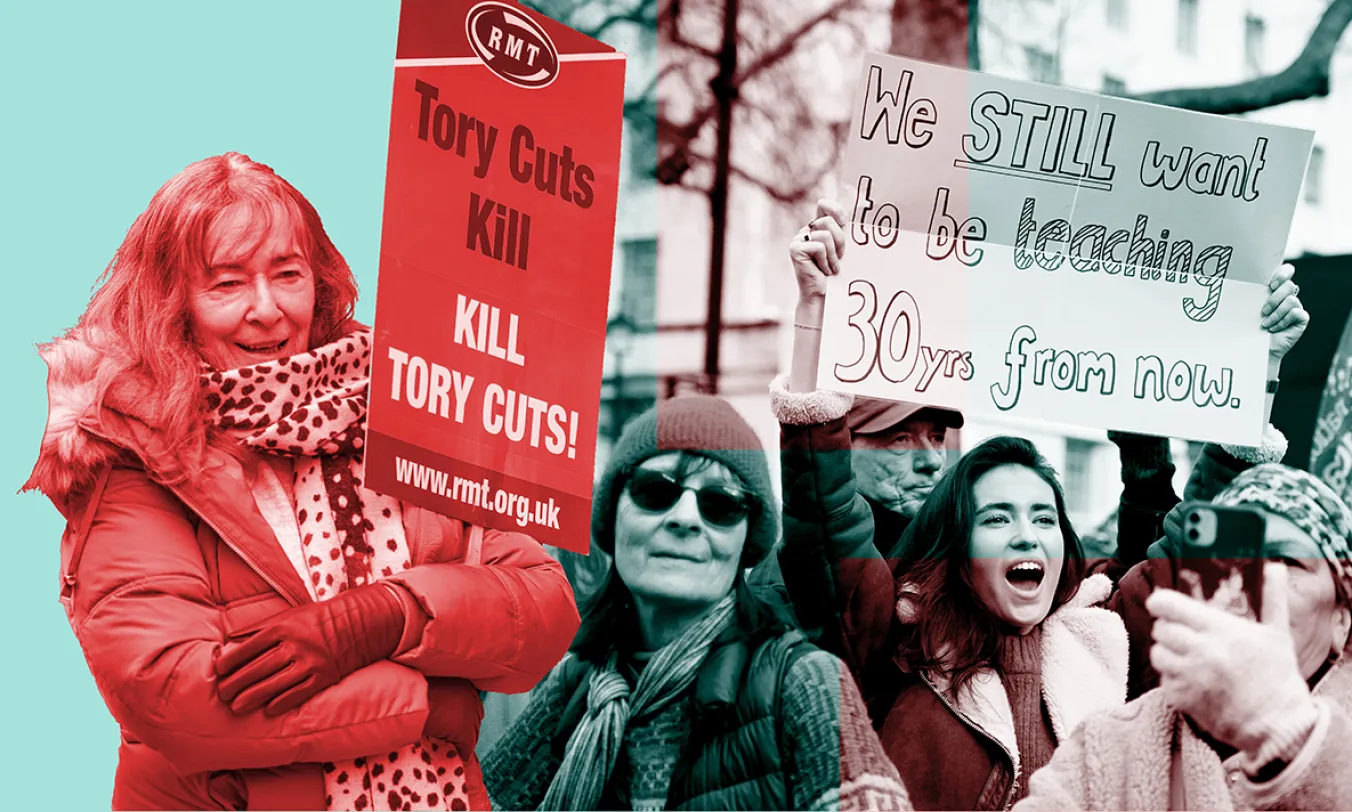

THE trade union movement has ignored women for much of its approximately 200-year history. This only began to change in the latter part of the 20th century. The fact that the late 1960s marks a turning point for women in the labour movement is due to a combination of two factors — the growing influence of the left in a number of key unions and the influence of the then vibrant women’s movement. The turning point in the late ’60s and early ’70s, was marked more by a change in attitude in that at long last women workers were perceived as having problems rather than being problems.

This led to a number of unions and the TUC itself looking at policy issues and structural changes to encourage greater participation and membership of trade unions by women. It is a process that could hardly be resisted once women organised and demonstrated their collective power, as for example in 1968 at Ford’s Dagenham plant when the women sewing machinists struck for pay regrading. Even more important was the equal pay victory won by women workers at Trico as a result of their historic strike in 1976.

However, the extent to which real change for women was brought about should not be exaggerated. What appeared as a forward march of women workers was, and still is, a process that can either be reversed or remain at the level of good intentions unless the forces that gave rise to it in the first place remain strong and united.