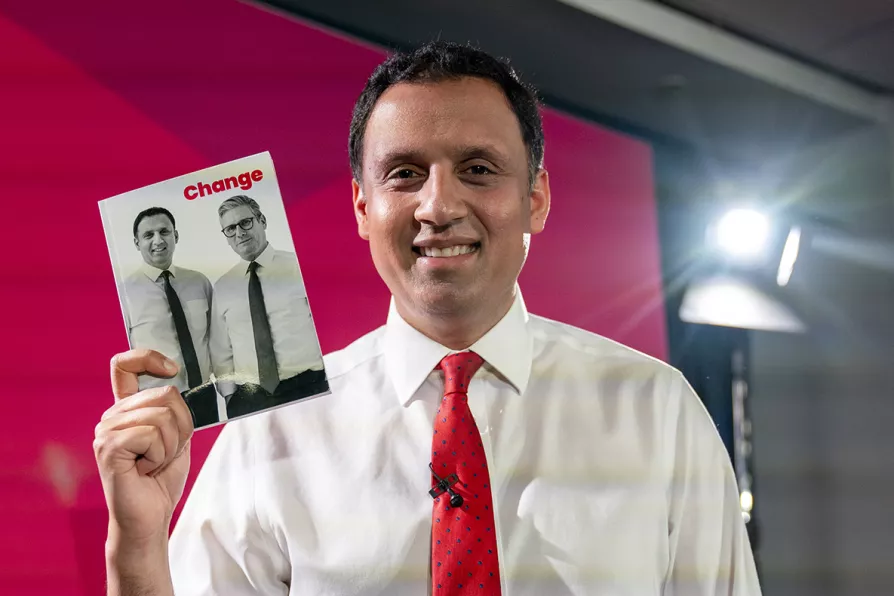

Scottish Labour leader Anas Sarwar speaking during the party's General Election manifesto launch at Murrayfield in Edinburgh, June 18, 2024

Scottish Labour leader Anas Sarwar speaking during the party's General Election manifesto launch at Murrayfield in Edinburgh, June 18, 2024

THE general election campaigns so far have been a mix of lacklustre manifestos from the main political parties — all failing to address the causes of worsening conditions in housing, healthcare and job opportunities.

Along with the constant drive to international war, we have fascistic rhetoric from the far right that denies any legitimate criticism of capitalism and the ruling class — instead turning it on the most vulnerable in our society, refugees.

However, the election does give a platform to progressive forces within the trade union and workers’ movements to highlight the systemic crisis felt by the working class in Britain and the growing distrust of Establishment politics.

The work done by Glasgow’s local campaigners and volunteers is truly inspiring, but it cannot stop at picking up the pieces of an irresponsible government, writes MAYA McGOWAN

Ahead of next year’s parliamentary elections, ROZ FOYER warns that a bold tax policy is needed to rebuild devastated public services which can serve as the foundation of a strong, fair economy

From Workers’ Memorial Day to May Day rallies, TOM MORRISON examines the real challenges facing the labour movement as Reform UK’s glossy literature exploits legitimate grievances in traditional left strongholds