Cuba, despite the privations, remains a beacon of sovereignty and resistance to imperialism, writes BERNARD REGAN

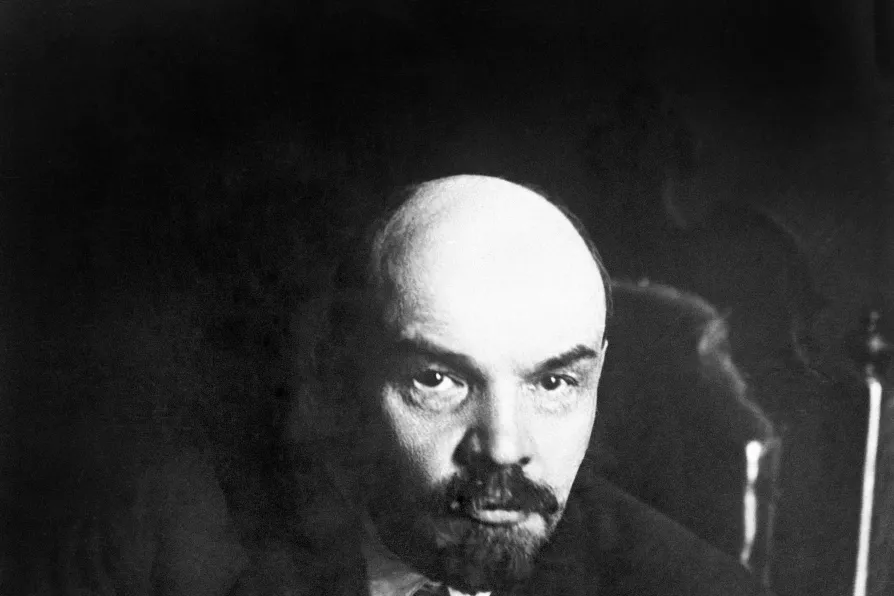

Vladimir Lenin, revolutionary leader of the first government of the USSR

Vladimir Lenin, revolutionary leader of the first government of the USSR

THE life of Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, founder of the world’s first socialist state, has been documented in more detail than perhaps any other historical figure — as proof, one need only cite the remarkable 13-volume Biographical Chronicle, compiled by the Communist Party of the Soviet Union’s Institute of Marxism-Leninism between 1970 and 1985. But even that meticulously compiled work is not exhaustive — for example, comparatively little is recorded there concerning the six visits Lenin made to Britain between 1902 and 1911.

Fortunately, in recent years some exciting archival discoveries have been made which throw more light on both the political and private life of Lenin during that period, and it is fitting that on the centenary of his death some of these discoveries should be published here.

There were two political figures in particular who featured prominently in Lenin’s life during his early visits to London whose names have been all but ignored by historians. These are the Russian social democrats Apollinariya Yakubova and her husband Konstantin Takhtarev, a young couple, previously known to Lenin from his time in St Petersburg, who had settled in the British capital three years before his first arrival in April 1902.

From hunting rare pamphlets at book sales to online panels and courses on trade unionism and class politics, the MML continues connecting archive treasures with the movements fighting for a better world, writes director MEIRIAN JUMP