The Carpathia isn’t coming to rescue this government still swimming in the mire, writes LINDA PENTZ GUNTER

MAT COWARD reminds us that the resilience of ordinary folk can turn the tables on the mighty and 'entitled'

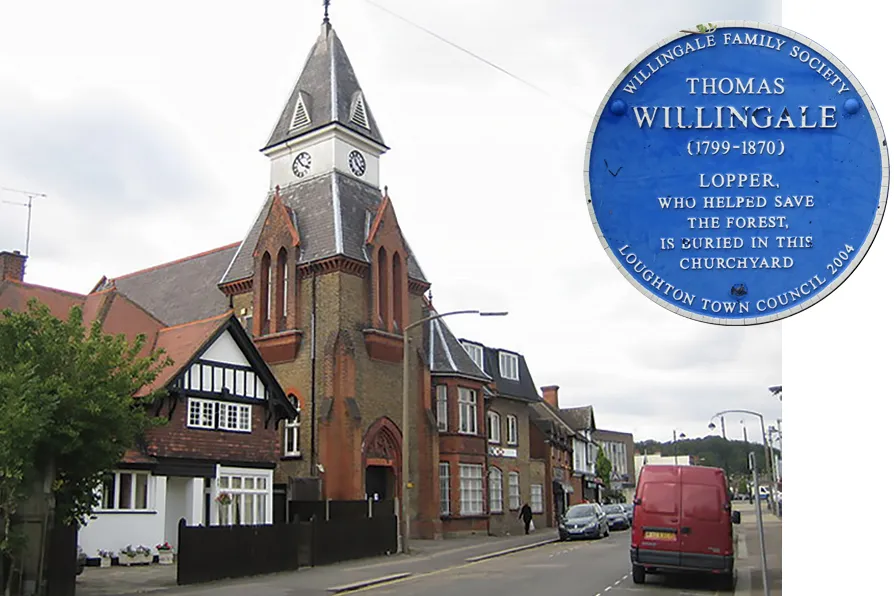

(L to R) Lopping Hall opened in 1884; Thomas Willingale plaque at St John the Baptist Church, Loughton, Essex / Pics: (L to R) Pic: Nigel Cox/geograph.org.uk/CC, Pic: Spudgun67/CC

(L to R) Lopping Hall opened in 1884; Thomas Willingale plaque at St John the Baptist Church, Loughton, Essex / Pics: (L to R) Pic: Nigel Cox/geograph.org.uk/CC, Pic: Spudgun67/CC

“HAD it not been for him there would have been no Epping Forest,” said a trustee of Lopping Hall in 1925, urging that a memorial be raised to the Loughton Lopper.

He wasn’t exaggerating: if you’re one of the several million who visit the forest every year, you might want to lift a glass to the glorious memory of Thomas Willingale (1798-1870), the illiterate labourer who took on the land-grabbers and won — and in doing so became posthumously one of the founding fathers of the international conservation movement.

Mind you, there are many myths and legends surrounding this story, of which my favourite is the loppers’ lock-in.

In the village of Loughton, in Essex, 19th-century residents were convinced (rightly or wrongly) that they had the right to “lop” trees in their local forest — that is, that according to ancient charter they were entitled to take branches for use as firewood.

There were plenty of restrictions, they acknowledged, such as not removing any wood lower than seven feet from the ground — and most importantly, that this right could only be exercised each winter between November 11 and April 23.

Crucially, if lopping failed to occur on the stroke of midnight on the 11th then the liberty to lop lapsed forever.

With this in mind, goes the story, in about 1860 the local lord of the manor invited all the active loppers to a pub supper, where he planned to get them so drunk that they’d never make it to their midnight appointment.

He’d reckoned without Thomas Willingale, who smelt a rat at their host’s uncharacteristic generosity.

Slipping out of the King’s Head in good time, he lopped his midnight branch and carried it back to the pub as evidence. (In some versions of the tale the wicked squire locked the loppers in, until valiant Thomas used his axe to smash down the door).

Whether or not any of that actually happened, it was indeed in the 1860s that the trouble started.

Enclosures of the forest, claiming common land as private and selling it to developers, had been going on for some time, led by local landowners the Maitland family, who were also big noises in the church.

Willingale was known for taking direct action against the enclosures — destroying fences and so on — and for carrying on lopping in defiance of the landlords’ orders.

In 1865 he was summoned by the Epping magistrates, charged with “injuring forest trees.” But the court heard evidence that lopping in the precise spot where the alleged offence took place had been carried out for generations without any interference. This enabled the defence that those charged had acted “under a fair and reasonable supposition” that what they were doing was legal. The case was dismissed.

The following year, however, one of his sons and two of his nephews faced similar charges and were convicted. They refused to pay the fine on principle and were jailed for a week with hard labour.

In response to this escalation in the local class war Thomas was urged to go to law himself, by the newly formed Commons Preservation Society (now called the Open Spaces Society).

The Society fought on many fronts: tearing down illegal fences, lobbying politicians, and supporting court cases.

Willingale v Maitland — in which Thomas claimed that lopping rights were being unlawfully withheld from “the labouring poor” — trundled unhurriedly through the Chancery courts and was still going when old Thomas died. He was buried in a pauper’s grave, he and his family having been evicted from their home and blacklisted by all local employers.

But by this time the conservationist cause was gaining unstoppable momentum; what had started as a struggle for survival by the poor was now supported by public figures and politicians of almost every stripe.

The Epping Forest Act of 1878 “disafforested” the forest by transferring control of it from the Crown to the Corporation of London.

The legislation specifically says that the few thousand acres remaining of what had once been the vast forest should now be “at all times uninclosed and unbuilt on, as an open space for the recreation and enjoyment of the public.”

It was a turning point and a precedent, in this country and beyond.

Enclosures of the forest became illegal — but so did lopping, largely for reasons of conservation. To compensate Loughton village for this loss, the Corporation of London paid for the building of Lopping Hall.

Opened in 1884, the hall still thrives as a marvellous community centre and venue for the people of the area. One of its well-equipped function rooms is named the Willingale Room. Loughton also contains a Willingale Road and a Thomas Willingale Primary School.

There used to be a pub, too, but in Chingford. In 1957 trades unionists in Essex argued that instead of naming a new boozer on a Loughton council estate after Sir Winston Churchill, the sign should depict someone with more local significance — such as Thomas Willingale.

They lost that fight, but rebels live forever, and old Thomas is well remembered.

As Punch put it, 50 years after the people won ownership of Epping: “Willingale a labourer, by lopping of a tree, kept houses off the Forest, for men like you and me.”

For more edifying stories visit https://rebelbrit.substack.com/