John Wojcik pays tribute to a black US activist who spent six decades at the forefront of struggles for voting rights, economic justice and peace – reshaping US politics and inspiring movements worldwide

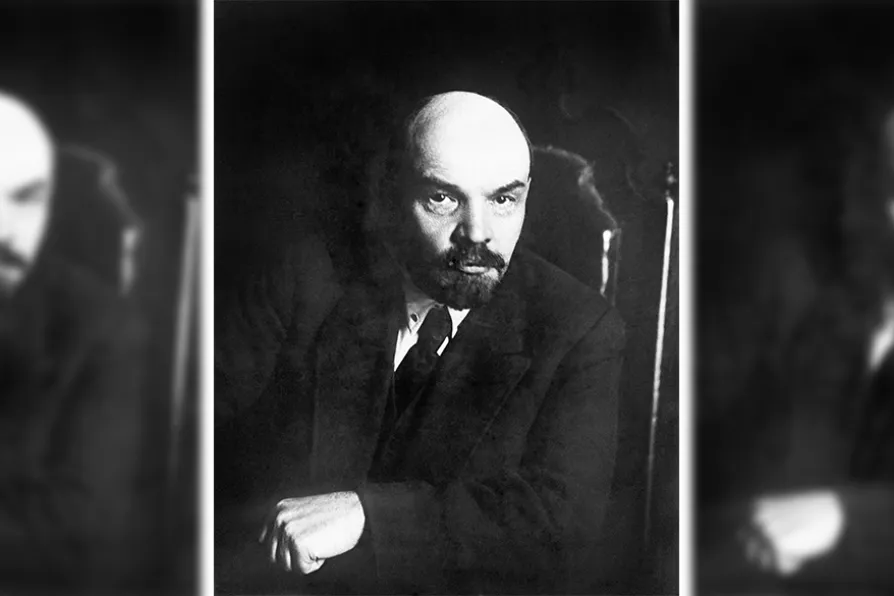

Vladimir Lenin, revolutionary leader of the first government of Soviet Russia, January 1921

Vladimir Lenin, revolutionary leader of the first government of Soviet Russia, January 1921

WHAT does history tell us about where we are today, well into the first half of the 21st century? It surely tells us that capitalism remains the greatest obstacle to solving the manifold injustices, irrationalities and existential threats that face humanity.

History also teaches us that the false answers of nationalism, racialism and social exclusion remain leading obstacles to overcoming capitalism and the class divide at the centre of capitalist social relations.

Division — the separation of potential allies in the struggle against capitalism — remains a deep infection immobilising those seeking social justice for all, a lesson the advocates of both casually chosen and deeply personal identities seem to have missed.

ISAAC SANEY points to the global stakes involved in defending the Cuban revolution against imperialism and calls for resistance

In 2024, 19 households grew richer by $1 trillion while 66 million households shared 3 per cent of wealth in the US, validating Marx’s prediction that capitalism ‘establishes an accumulation of misery corresponding with accumulation of capital,’ writes ZOLTAN ZIGEDY