The Carpathia isn’t coming to rescue this government still swimming in the mire, writes LINDA PENTZ GUNTER

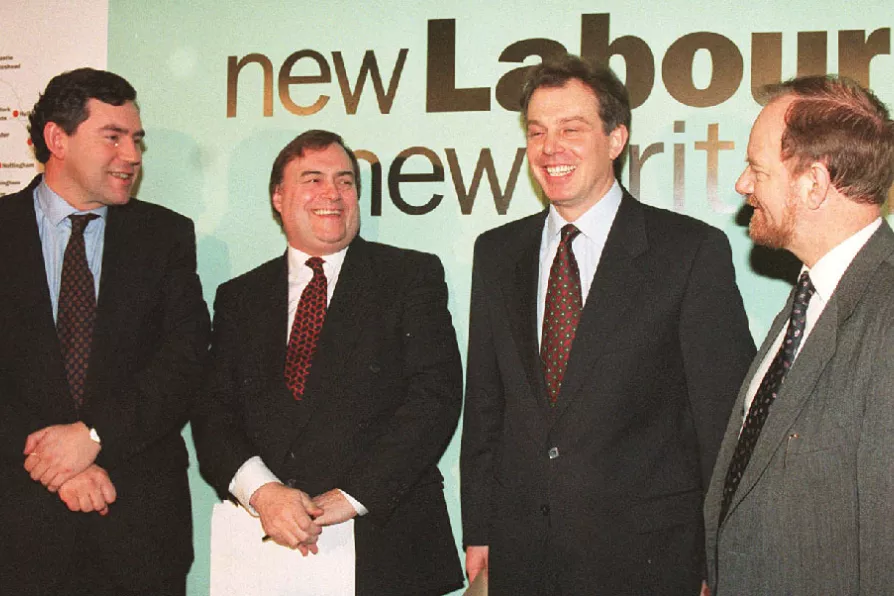

NEW FOR OLD? Labour leader Tony Blair (second right), with (from

left) Gordon Brown, deputy leader John Prescott and Robin Cook at

the 1995 launch of the ‘New Labour, New Britain’ tour, in which he

spent three weeks visiting towns and cities in a bid to convince party

doubters that clause four of the party’s constitution must be scrapped

NEW FOR OLD? Labour leader Tony Blair (second right), with (from

left) Gordon Brown, deputy leader John Prescott and Robin Cook at

the 1995 launch of the ‘New Labour, New Britain’ tour, in which he

spent three weeks visiting towns and cities in a bid to convince party

doubters that clause four of the party’s constitution must be scrapped

THE tributes have for have been pouring for political heavyweight and man of the people, John Prescott (aka Baron Prescott of Kingston upon Hull), who passed away last week aged 84.

His reputation was of a man singularly able to cut through the usual Westminster crap using the unvarnished spade of mangled syntax and the blunt shovel of malapropisms as his tools.

Homeless seamen were forced to live in “hostiles,” industrial disputes could be sorted through “meditation,” and the New Labour mission was to “go back now, forwards, back to full employment.” Absolute gibberish, of course, but we knew what he was on about, at least most of the time.

Every Starmer boast about removing asylum-seekers probably wins Reform another seat while Labour loses more voters to Lib Dems, Greens and nationalists than to the far right — the disaster facing Labour is the leadership’s fault, writes DIANE ABBOTT MP

The Tories’ trouble is rooted in the British capitalist Establishment now being more disoriented and uncertain of its social mission than before, argues ANDREW MURRAY

With Reform UK surging and Labour determined not to offer anything different from the status quo, a clear opportunity opens for the left, argues CLAUDIA WEBBE