culture

culture

Culture: A New World History

Martin Puchner

Ithaca, £12.99

MARTIN PUCHNER’S Culture: A New World History manages to achieve something not all histories do: to make you come away feeling that you’ve learnt something.

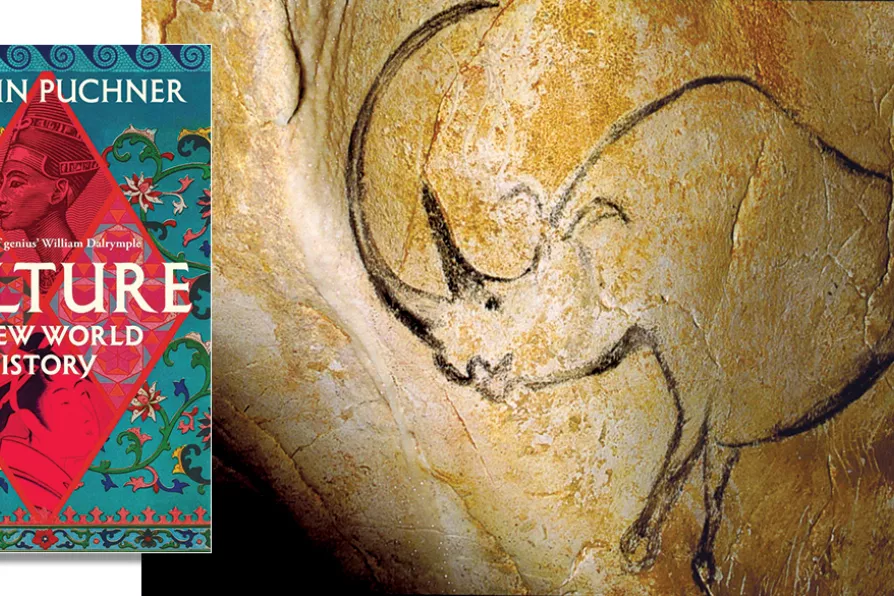

The book’s strength lies in its storytelling as a narrative history constructed from 15 chronological episodes that the author sees as emblematic of the varying ways in which culture has been created, used, discarded and rediscovered, going back to the 14th century BCE. As well as that, the book is framed by an introduction on the Chauvet Cave from 35,000 BCE and an epilogue about the future of the library in the digital age.

Among other things, we learn about the bust of Nefertiti, the Japanese Pillow Book, the Storehouse of Wisdom in Baghdad, the Ethiopian Kebra Nagast, Hildegard of Bingen, Moctezuma and the Aztec Empire, Toussaint L’Ouverture and George Elliot’s role in the origin of historiography. His focus is on visual and performing arts, plus to a lesser degree, literature, so there’s no real discussion of music, and none of film, though given that the latter is only turning 130 next year, so he can be forgiven for that.