DR HANA SAADA asks why a war crime against innocent children on this scale does not dominate the world’s coverage of the US-Israeli war on Iran

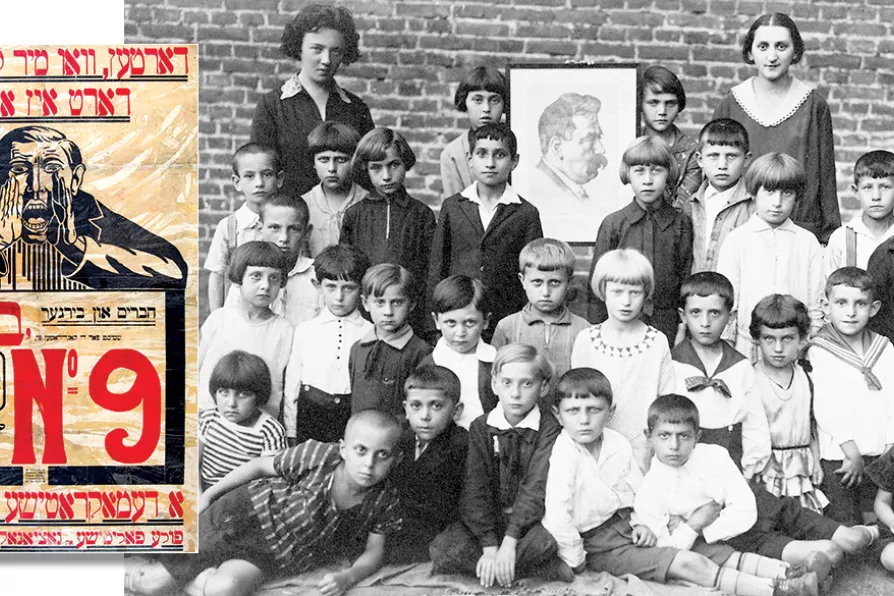

NOBLE ASPIRATIONS: (Left) ’Where we live, there is our country! Vote List 9, Bund’ and ‘A democratic republic! Full national and political rights for Jews!,’ Bund election poster in Kiev, 1917; (below) Group portrait of the first-grade class of the Bundist school in Kalisz, central Poland, 1930-1934

[Public Domain]

NOBLE ASPIRATIONS: (Left) ’Where we live, there is our country! Vote List 9, Bund’ and ‘A democratic republic! Full national and political rights for Jews!,’ Bund election poster in Kiev, 1917; (below) Group portrait of the first-grade class of the Bundist school in Kalisz, central Poland, 1930-1934

[Public Domain]

LAST Saturday’s huge demonstration against the war on Gaza and for justice for Palestine was remarkable. Overwhelmingly young, multicultural, energetic and united, it had another striking phenomenon, missing from mainstream media reports.

Despite the rhetoric of politicians, media commentators and Jewish community “leaders” claiming that a pro-Palestine march through central London would be a huge affront and danger to Jews, right there among the marchers was a large Jewish bloc, mobilised by several different groups.

This wasn’t the first time that Jews from different organisations were marching for Palestinian rights and justice, but the scale, demography, and spirit was different.

With foreign media banned from Gaza, Palestinians themselves have reversed most of zionism’s century-long propaganda gains in just two years — this is why Israel has killed 270 journalists since October 2023, explains RAMZY BAROUD