ALAN SIMPSON offers a few pointers on dealing with the ongoing, Trump-led destruction of the norms of a rules-based international order established post-WWII

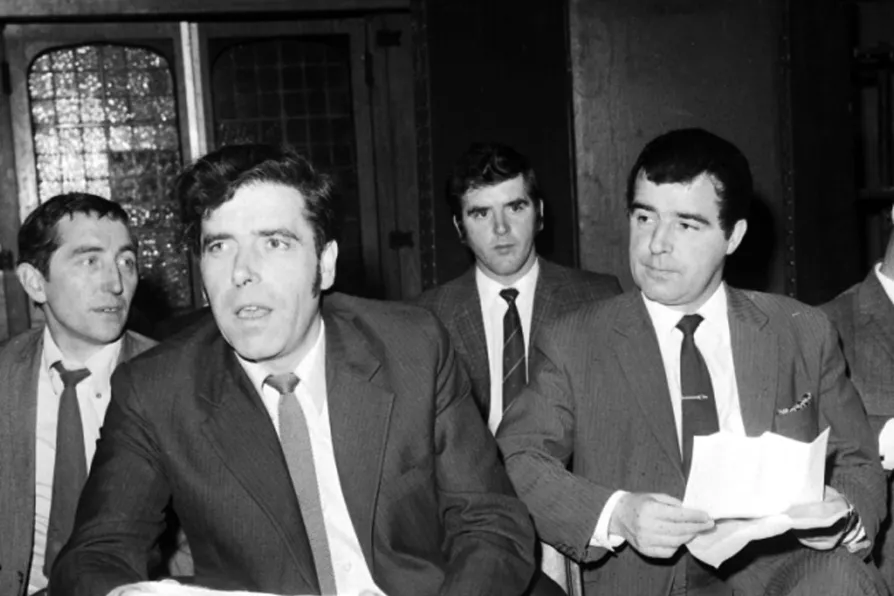

James Reid (left foreground) chief spokesman for shop stewards, and James Airlie (right), co-ordinator, shop stewards’ committee, during a press conference, 1971

James Reid (left foreground) chief spokesman for shop stewards, and James Airlie (right), co-ordinator, shop stewards’ committee, during a press conference, 1971

IN JULY 1971 8,500 shipyard workers took control of four shipyards on the Upper Clyde: Govan, Linthouse, Scotstoun and Clydebank to stop their closure.

The shop stewards remained in control of the yards for the following 15 months and only ended their “work-in” when the government had fully capitulated and financially guaranteed the survival of all four yards.

This action on the Clyde had a much wider national impact. The Tory government was alarmed at the growing shop stewards’ militancy with good cause, as the workers’ successful enforcement of their right to work gave encouragement to workers in hundreds of other workplaces facing closure during the recession years of 1971-73.

In part II of a serialisation of his new book, JOHN McINALLY explores how witch-hunting drives took hold in the Civil Service as the cold war emerged in the wake of WWII

In the run-up to the Communist Party congress in November ROB GRIFFITHS outlines a few ideas regarding its participation in the elections of May 2026

From Workers’ Memorial Day to May Day rallies, TOM MORRISON examines the real challenges facing the labour movement as Reform UK’s glossy literature exploits legitimate grievances in traditional left strongholds