RON JACOBS welcomes a timely history of the Anti Imperialist league of America, and the role that culture played in their politics

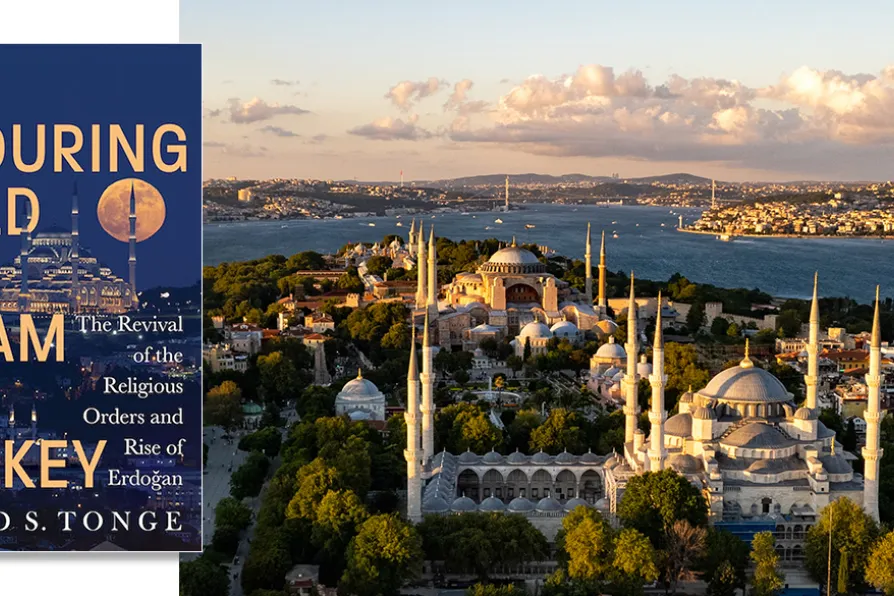

Istanbul's Hagia Sofia Mosque

[Hunanuk/CC]

Istanbul's Hagia Sofia Mosque

[Hunanuk/CC]

The enduring hold of Islam in Turkey

David S Tonge, Hurst, £45

IF you can stand it, this book relays a sobering and detailed analysis of the competing religious alliances behind the ascendancy of conservative nationalism in today’s Turkey — a tale that is couched in such a wealth of obscure Islamic language and names as to be almost incomprehensible.

But it packs a punch in its introduction and concluding chapters. Here President Erdogan seals the symbolic fusion of the hitherto secular state with Islam by reopening the vast Ayasofya mosque in Istanbul as a Muslim centre of worship. Religious use of the building had been prohibited since 1935, and the days of Ataturk’s determined secularisation of the Turkish state.

This book details the provenance of religious groups from the end of the Ottoman empire onwards, the measures taken to suppress them in the 20th century, and their re-emergence as a political force in the 21st. It’s a complex story of religious factionalism on the political right. You need a working knowledge of Turkish history to keep up with David Tonge’s account of events from this little-known perspective, and to get some sense of what Turkish democracy has evolved into since the introduction of multiparty elections in 1950. The perspective of left political organising is absent from this account, and the whole book is the weaker for it.

ALEX HALL follows the battered fortunes of Syria, a multi-ethnic country caught in the crossfire of competing imperialist interests