With more people dying each year and many spending their final days in institutions, researchers argue that wider access to palliative care could offer a more humane and cost-effective alternative, write ROX MIDDLETON, LIAM SHAW and MIRIAM GAUNTLETT

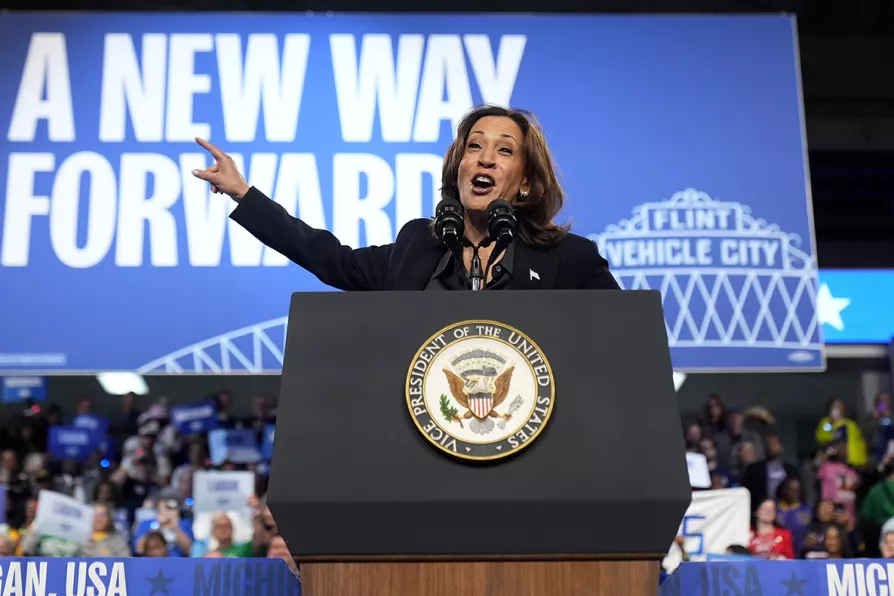

Democratic US presidential nominee Vice President Kamala Harris speaks during a rally at the Dort Financial Centre in Flint, Michigan, October 4, 2024

Democratic US presidential nominee Vice President Kamala Harris speaks during a rally at the Dort Financial Centre in Flint, Michigan, October 4, 2024

DONALD TRUMP calls her “comrade Kamala.” Unfortunately, she is anything but.

US Vice-President Kamala Harris, the unexpected Democratic presidential candidate after incumbent Joe Biden dropped out of the race on July 21, is following a studiously moderate path to the White House.

Time will tell whether her centrist positions on issues like climate, immigration and even Gaza are designed to draw in conservative voters who are not extreme enough to embrace Trump, or whether they will translate into presidential policies should she win in November.

While Harris has occasionally made stronger statements on Gaza than Biden, she has not acted to end the violence there by insisting the US halt its transfer of weapons to Israel. Biden has remained notably in the background since his decision not to run for a second term, yet Harris is clearly not at the helm yet.

The Vice-President has also embraced fracking, something she favoured banning while a US senator. The shift may be to placate voters in states such as Pennsylvania where fracking is a major industry. But it also demonstrates a shocking denial of the most recent climate crisis-induced catastrophe brought on by Hurricane Helene that has ravaged large parts of the country’s south.

And on immigration, where Harris once fought for decriminalising border crossings, she now advocates extending the current restrictions on asylum-seekers, a crackdown that comes without provision for any additional pathways to citizenship.

All of this has left more progressive voters in the Democratic Party somewhat in limbo, especially those who voted “uncommitted” during the earlier primaries before Harris was the candidate. That stance was designed to send a message to Biden that he must act to end Israel’s violence in Gaza, the West Bank and now Lebanon. But it didn’t work.

At the Democratic national convention in August, the uncommitted movement still held out hope that Harris would deliver not only stronger rhetoric but stronger policies to curb Israel’s aggression, but that hasn’t happened.

After staging a sit-in at the convention, the group gave Harris until September 15 to meet them. The deadline came and went. On September 18, the group reluctantly announced they would not endorse Harris for president.

“Vice-President Harris’s unwillingness to shift on unconditional weapons policy or to even make a clear statement in support of upholding existing US and international human rights law has made it impossible to endorse her,” said Abbas Alawieh, one of the founders of the uncommitted movement.

On Capitol Hill, most of the more left-leaning legislators, including democratic socialist senator Bernie Sanders, an independent, are supporting the Harris campaign, even though they differ widely on some progressive policies. Sanders justifies his support for Harris, saying she is “doing what she thinks is right in order to win the election.”

The critical necessity to defeat Trump has caused many on the left to “hold their nose” and support Harris, one Democratic strategist told the Washington Post, “because they’re like, whatever it takes to get you to win.”

That number includes one of the more radical members of Congress, Ilhan Omar, a Somali immigrant representing Minnesota. But even Omar, who said “It’s about organising and seeing how far we can push her once she wins the presidency,” isn’t entirely optimistic.

“I believe there is a great appreciation in the empathy and compassion that she offers,” Omar said of Harris during a CNN interview last month when discussing a ceasefire in Gaza. But, she added, “to say we are working around the clock and not take any actionable steps that the voters and the US people can see makes that rhetoric really hard to swallow.”

Linda Pentz Gunter is a writer based in Takoma Park, Maryland.

Mask-off outbursts by Maga insiders and most strikingly, the destruction and reconstruction of the presidential seat, with a huge new $300m ballroom, means Trump isn’t planning to leave the White House when his term ends, writes LINDA PENTZ GUNTER

From terrifying the children of immigrants to pepper-spraying frogs, the US under Trump is rapidly descending into mayhem, writes Linda Pentz Gunter

LINDA PENTZ GUNTER reports from London’s massive demonstration, where Iranian flags joined Palestinian banners and protesters warned of the dangers of escalation by the US, only hours before a fresh phase of the war began