CONRAD LANDIN thrills to the voice of 79-year-old Emmylou Harris, that is enriched rather than compromised by the gravel of experience

RICHARD MURGATROYD enjoys a readable account of the life and meditations of one of the few Roman emperors with a good reputation

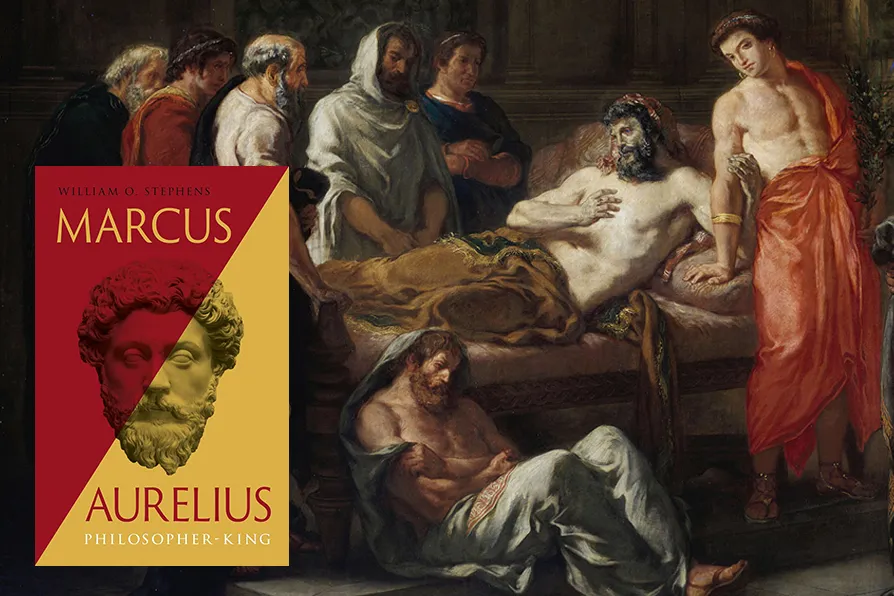

FATAL MISJUDGEMENT: Eugene Delacroix, Last Words of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius, 1844 [Pic: Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon/CC]

FATAL MISJUDGEMENT: Eugene Delacroix, Last Words of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius, 1844 [Pic: Museum of Fine Arts of Lyon/CC]

Marcus Aurelius: Philosopher-King

William O Stephens, Reaktion books, £15.99

WE usually only remember the names of the “bad” Roman emperors. Like Nero, who fiddled while Rome burnt and murdered his mum. Caligula, who slept with all three of his sisters and appointed his favourite racehorse to the Senate to show his contempt for that august body. The “good” ones are harder to spot. Probably only Marcus Aurelius springs to mind.

Marcus’s reputation largely rests on a small book called the Meditations. This records his private thoughts and feelings as he struggles to reconcile his role as emperor of Rome with his deeply felt personal philosophy. It was never intended for publication. The Meditations have been a bestseller for centuries because Marcus tackles difficult questions about life, relevant to every human being.

Marcus was deeply into Stoic philosophy. The term “stoic” has now entered the English language to mean someone who endures pain without complaint and accepts their fate. This was certainly an aspect of ancient Stoicism but perhaps the least important. Stoics aimed at self-mastery of the unruly mind and heart by cultivating a “passionless” self-sufficiency. This emphasis on self-help left little room for social criticism and turned attention onto the individual. It’s no wonder many modern conservatives are attracted by Stoicism.

However, there was also a progressive side. Ancient Stoics argued that wealth, honours and vanity were futile. We should live simply so we should simply live. Moreover, we are all interconnected. This “cosmopolitanism” means that all human beings are “fellow citizens of the universe … bound together into a cosmic community and universal commonwealth” irrespective of class, ethnicity, family or gender. A sort of equal opportunity Stoicism?

Marcus genuinely attempted to address these ideas in his notebook. His language is direct and sincere, his pain and puzzlement on display — it’s easy to see why the Meditations have proven so popular. But did his actions match these high ideals? William O Stephens’ biography attempts to answer that question by diving deep into the original sources. The result is a scholarly but very readable description of Marcus’s life and times.

Marcus was born into the highest levels of the Roman aristocracy and adopted by the emperor Antonius Pius as heir. After a glittering political career he ascended to the throne in 161 CE aged 40. He only agreed to rule alongside his younger brother, which Stephens claims shows his natural modesty. However, once installed he clung tenaciously onto power, violently crushing several attempts to remove him.

Leaving aside the dirty politics of the Roman elite, Marcus certainly faced problems that would test the equanimity of any Stoic. The empire was ravaged by a devastating pandemic that lasted for decades. Worse, “barbarian” tribes united and attacked the Western Rhine and Danube borders. He therefore spent most of his 19-year reign at war. After a hard day’s work trying to kill, enslave and outfox the brutish barbarian hordes, Marcus would retire to his tent in a muddy army camp and compose his meditations.

But the consolations of philosophy have their limits and the pressure eventually told. His health broke down and he developed something of a drug problem. Although it was clear that his only surviving son Commodus was unsuited to rule, Marcus insisted on the hereditary principle. So, when he died in 180 CE Commodus become another spectacularly “bad” emperor to rival Nero and Caligula.

While Stephens is clearly a fan he doesn’t shy away from awkward facts. In particular, it’s hard to reconcile Marcus’s brutal military campaigns with Stoic ideals. Nor does the mass enslavement of the resulting “barbarian” prisoners, shipped off to serve as forced labourers on the estates of his fellow aristocrats, sit well. Similarly, Marcus’s love of free philosophical debate didn’t extend to Christians and other dissident minorities who faced violent persecution.

Should we then dismiss Marcus as a hypocrite? Stephens asks us to see him as a man of his time, doing the best he could in very difficult circumstances. Given his track record as a ruler, it’s hard to agree. So, we are left with the Meditations, which are probably still enough to secure Marcus’s reputation as a “good” emperor, however undeserved.