In his second round-up, EWAN CAMERON picks excellent solo shows that deal with Scottishness, Englishness and race as highlights

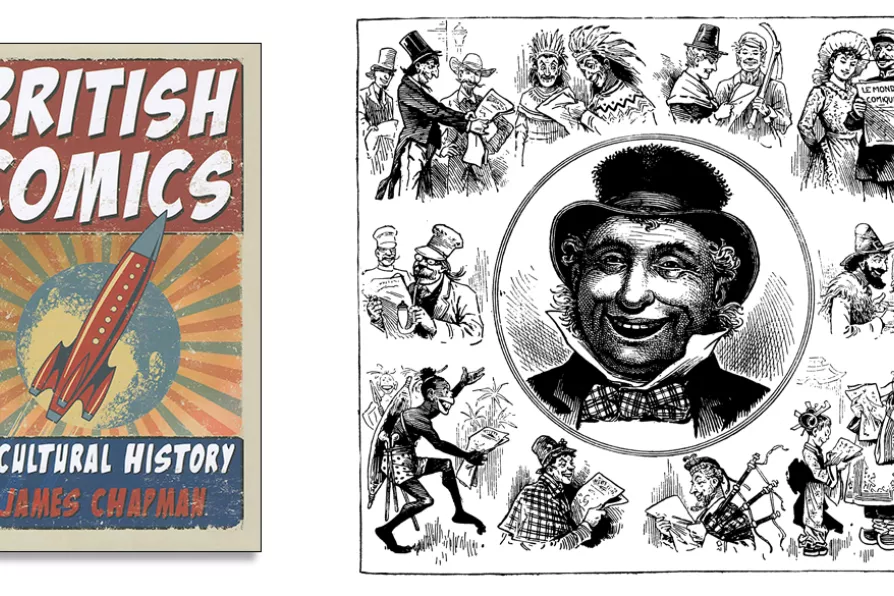

The cover of The World's Comics 1, July 6 1892

[Public Domain]

The cover of The World's Comics 1, July 6 1892

[Public Domain] British Comics: A Cultural History

James Chapman, Reaktion, £15

RECENTLY published in paperback, this entertaining, thoughtful and detailed analysis of British comics from the late Victorian period to the present day is not to be missed. Written with insight and passion, if you don’t see yourself as interested in comic books then this might well be the text to get you started.

And let’s be honest, comics haven’t had a very good press, not just from mainstream commentators but from many on the left. Depicted as the worst of an already low and trashy culture, they have often been labelled violently right-wing, racist and misogynistic so much so that in the late 1940s and ’50s the Communist Party of Great Britain joined hands with some unlikely allies to campaign against what were seen as reactionary and effectively pro-imperialist imports.

At the very moment Britain faces poverty, housing and climate crises requiring radical solutions, the liberal press promotes ideologically narrow books while marginalising authors who offer the most accurate understanding of change, writes IAN SINCLAIR