ALISTAIR FINDLAY recommends the simple cadence, common prose, free verse, and descriptive power of a new collection by Julie McNeill

MARTIN HALL welcomes a study of Britain’s relationship with the EU that sheds light on the way euroscepticism moved from the margins to the centre

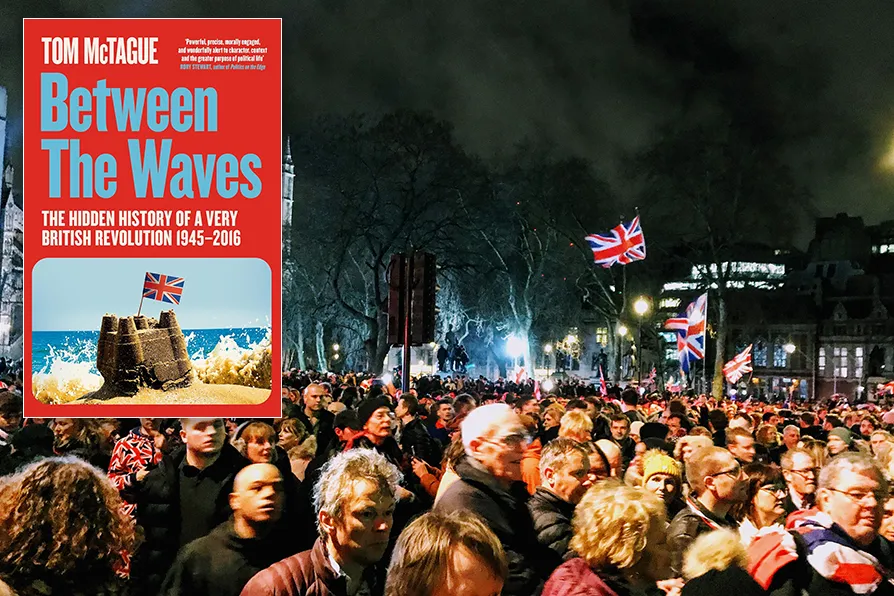

Thousands gathered in Parliament Square to mark the moment that the UK officially left the EU, January 31, 2020 [Pic: Andrew Davidson/CC]

Thousands gathered in Parliament Square to mark the moment that the UK officially left the EU, January 31, 2020 [Pic: Andrew Davidson/CC]

Between the Waves: The Hidden History of a Very British Revolution 1945-2016

Tom McTague, Picador, £25

SINCE Brexit, it is relatively rare for a contribution on Britain’s relationship with the EU to shed light, rather than add to the fog of misunderstanding, so Tom McTague’s new book makes a very welcome change. Taking the longer view from post-WWII to the 2016 referendum, it charts the British journey from “no thanks” to in-but-on-its-own-terms, and back again.

Of particular value is his analysis of the insistence on British exceptionalism being wired-in from the outset. The book charts how prime minister after prime minister, with Ted Heath as the odd one out, attempted to maintain a creative ambiguity regarding the extent of British involvement, with economic benefits prioritised and political integration wilfully ignored, or sidelined.

This is a welcome rejoinder to those who argue that such exceptionalism is only to be found among right-wing leavers and other hangovers from the empire. Indeed, it is remarkable how many instances there are in the book of prime ministers and other senior members of the executive not looking at what was often in black and white in front of their noses in the documents they were examining, namely: that the project was, from the outset, a plan for a greater Europe with the obvious attendant reductions in national sovereignty. It would, of course, be peculiar if anything else were the case, given the institution’s origins in the horror of war.

Yet this misunderstanding persisted. Why?

While McTague’s analysis doesn’t draw the conclusions that a socialist critique of the topic would, not least due to a differing view of imperialism, he does situate this in/out predisposition in Britain’s struggle to grapple with its post-war decline, which was concomitant with the growth of the “special relationship” with the US.

We begin outside Europe, though, in a city and country still under colonial rule: French-run Algiers at the end of 1942. Three men, central to the idea of Europe, were there: Jean Monnet, the inventor, if such a term can be used, of the European idea in its modern form; Charles de Gaulle, the future French prime minister with a different idea of Europe; and Harold Macmillan, future British PM and the first to attempt to join the European bloc.

In the wings, though — and a significantly less senior figure at the time — was Enoch Powell, perhaps the single most important figure in British euroscepticism, certainly for the right.

McTague uses this reconstruction as a plot device to launch into a narrative history, but not one without an eye on a structural approach that emphasises more general trends. This makes it an entertaining read for the general reader while also being of value to the specialist.

Regarding euroscepticism, as is to be expected, the principal focus throughout is on its right-wing formulation. The author traces the growth of what was a minority current in British conservatism to its hegemonic position now. We see that actual withdrawal was not the aim of many of the Brexit campaign’s principal figures until quite late in the game, with focus instead being on, for example, staying out of monetary union in the ‘90s and ‘00s.

That said, there is also time given to left euroscepticism and its opposite direction down the European path: from a majority current to a minor one. He correctly situates that journey as one whose predicate was defeat, coming on the back of Thatcher’s victories over the miners and the print workers at the local level, and the defeat of socialism in Europe at the continental level. This was crystallised, as is well known, following Jacques Delors’s outlining of a social Europe to the TUC in 1988.

Of course, that veneer of rights was a major factor in Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher’s increasing euroscepticism, culminating in her downfall in 1990 and replacement with John Major, who continued the British policy of wanting to be in, but on Britain’s own terms.

The twisting road to Brexit makes up the remainder of the book. We see the rise in Tory student politics of Dominic Cummings, Michael Gove and Boris Johnson, as well as less well-known figures such as Dougie Smith, and time is given to the intellectual ballast that underlay it, initially situated in the Oakeshottian Conservative Philosophy Group comprising, among others, Hugh Fraser, Maurice Cowling and Edward Norman, along with younger academics such as Roger Scruton and Norman Stone.

This is particularly important given the paucity of the debate in 2016, which descended into a culture war that is still not over in British politics. Indeed, a major strength of the book is that is holds back from taking a position in that tortuous conflict.

Rather, we are given a stimulating piece of long-form journalism that will encourage readers on both sides of the European question to examine their own positions, without any overt attempt to change them. For that if nothing else, it should be as widely read as possible.

MARTIN HALL passes time in the sanguine company of a traditional conservative, recalling their disastrous governments

A bizarre on-air rant by Sebastian Gorka, Trump’s head of counter-terrorism, shines a light on the present state of transatlantic relations, says NICK WRIGHT

JOHN ELLISON recalls the momentous role of the French resistance during WWII