VIJAY PRASHAD examines why in 2018 Washington started to take an increasingly belligerent stance towards ‘near peer rivals’ – Russa and China – with far-reaching geopolitical effects

More than just funny food and a stern face

MAT COWARD remembers the curious character of Sir Stafford Cripps, who was Winston Churchill's ambassador to the Soviet Union, with a famously eccentric diet

THE apparent link between digestive troubles and radicalism is often noted, though rarely pursued with any kind of scientific rigour.

Are people with bothersome guts disproportionately drawn to the revolutionary cause? Or do leftwingers develop such symptoms from worrying about the state of the world? Or is the whole thing a statistical illusion — the result, if you’ll pardon the expression, of relying on too small a sample size?

Whatever the case, “Sir Stifford Crapps” was an inevitable nickname for a man as famous for his asceticism and his stomach problems as for his political actions.

More from this author

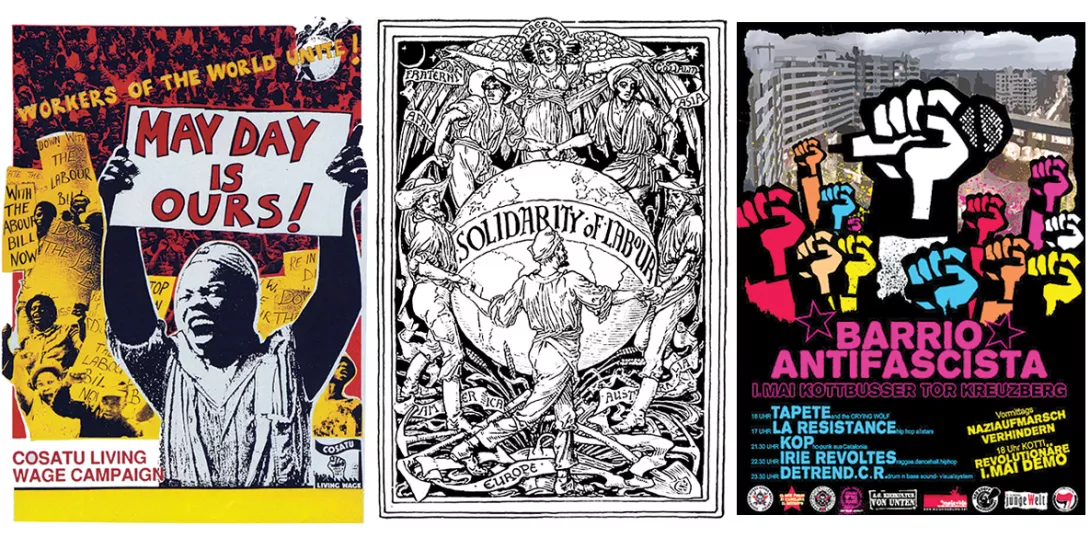

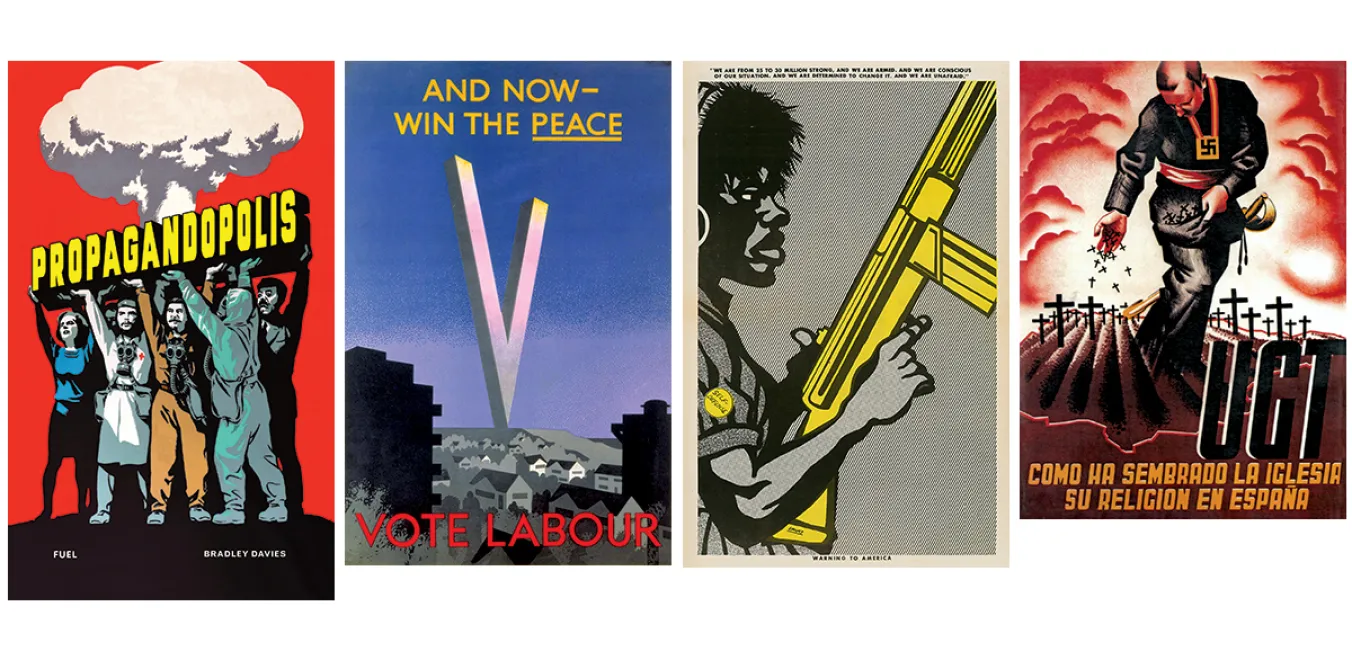

MICHAL BONCZA recommends a compact volume that charts the art of propagating ideas across the 20th century

MICHAL BONCZA reviews Cairokee gig at the London Barbican

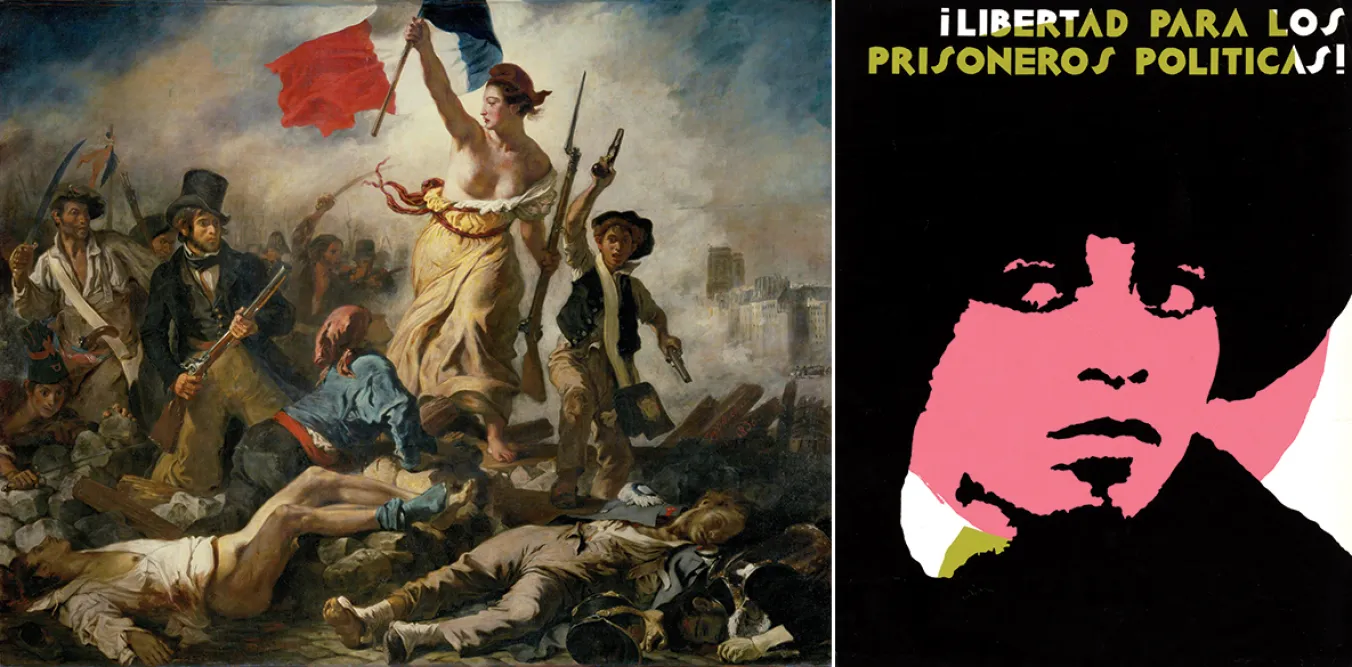

MICHAL BONCZA rounds up a series of images designed to inspire women

Similar stories

A crucial part of the war effort, the Home Guard, was launched partly due to the influence of Tom Wintringham, a revolutionary communist with a passion for DIY grenades and guerilla warfare, writes MAT COWARD

Taking up social work after being widowed transformed a Victorian liberal into a lifelong fighter for causes as wide-ranging as Sinn Fein and Indian independence to the right of women to drink in pubs, writes MAT COWARD

MAT COWARD resurrects the radical spirit of early Labour’s overlooked matriarch, whose tireless activism and financial support laid the foundations for the party’s early success

Normally in British politics, leftwingers defect right. Under Blair and now Starmer however, this trend seems to reverse, calling into question the ‘broad church’ that welcomes Tories and excludes socialists, writes KEITH FLETT