Corbyn’s intervention exposes a corrupted system, writes CLAUDIA WEBBE

80 years on, JOHN HAWKINS reflects on the terrible lessons of the second bombing — and the way AI is advancing an era of automated destruction

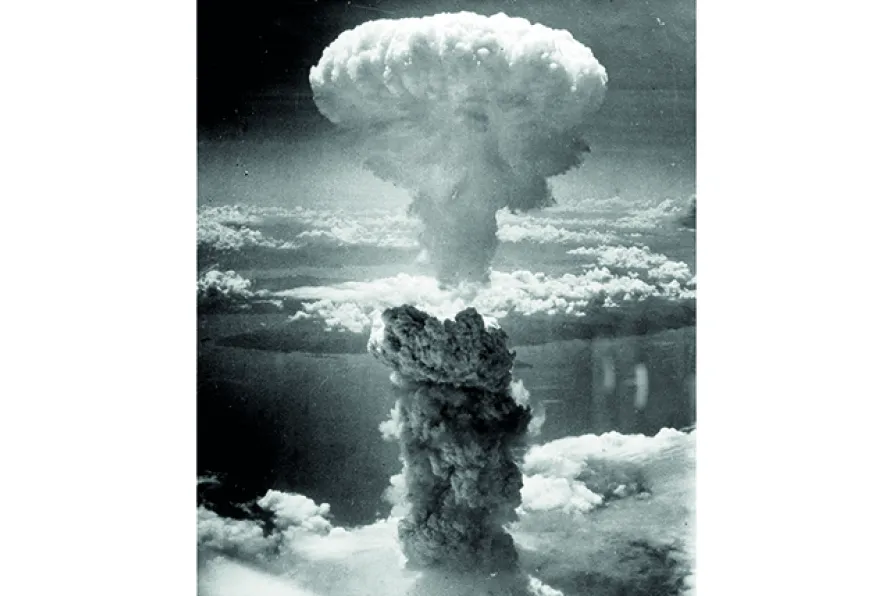

The mushroom cloud from the Nagasaki bomb blast

The mushroom cloud from the Nagasaki bomb blast

ON AUGUST 9 1945, the second atomic bomb fell on the city of Nagasaki.

If Hiroshima signalled the dawn of the nuclear age, Nagasaki declared our species’ willingness to annihilate itself not once, but twice.

Hiroshima was a fission bomb. Nagasaki, the more complicated and ominous of the two, was a fusion bomb — a weapon that used a fission explosion to trigger an even greater release of energy. It was, in essence, a proof-of-concept for the hydrogen bomb: a gateway to planetary death.

Scientists at Los Alamos had nervously joked before the Trinity test about the possibility that their creation might ignite the atmosphere or vaporise the oceans — not just because of what they knew, but because of what they didn’t. The possibility of the apocalypse hung over them not as an abstraction, but as a statistical uncertainty.

Edward Teller reportedly considered it a non-zero risk. As Daniel Ellsberg recounts in The Doomsday Machine, “[B]y late July the scientists had demonstrated their own readiness to take a sufficiently small chance (for [Enrico] Fermi, not so small) of burning up all life on the planet.” (Ellsberg describes how Fermi, in a fit of black humour, was “making book” on the odds of the fusion bomb blowing up the world).

Ellsberg had always regarded the information in Doomsday as more important than The Pentagon Papers, and he had intended to release it first. When Ellsberg later reflected on the bomb-building period, he recalled walking out of Dr Strangelove with a Rand corporation colleague: “We came out into the afternoon sunlight, dazed by the light and the film, both agreeing that what we had just seen was, essentially, a documentary.”

Nagasaki should have ended all talk of nuclear war. Instead, it formalised it.

Unlike Hiroshima, which has come to symbolise peace and remembrance, Nagasaki is the forgotten warning — the second strike, the unnecessary blow.

But in the context of 20th-century madness, that excess is the point. Erich Fromm, in The Anatomy of Human Destructiveness, traced this excess to a death instinct — not merely in the Freudian sense of the Thanatos drive that opposes Eros, but in the pathology of a species fixated on its own self-destruction. Freud himself, in Civilisation and Its Discontents, had already seen that civilisation may be the very structure that represses us into neurosis and destruction.

Nagasaki wasn’t only a strategic target; it was also a theological one.

The city’s large Catholic population and symbolic status in Japan’s small Christian community gave the strike a grotesque poignancy — a crucifixion without resurrection. Reports tell of “shadow people,” whose silhouettes were burned into stone and cement by the intensity of the blast. For many people, these weren’t metaphors. They were literal: negative-space remains of people who, in an instant, were vaporised into history. But the claim of shadows etched in stone is still contentious.

The firebombing of Tokyo earlier that year had already killed over 100,000 in one night, through conventional means — gasoline, magnesium, and wind. But nuclear weapons changed the equation, not only in destructive scale, but in metaphysical weight. What the firebombing suggested, the atomic bomb confirmed: the line had been crossed.

And it was a scientist’s line, a planner’s line — a product of the Enlightenment turned feral. All told, it is estimated that approximately 400,000 Japanese people were killed as a result of the bombings, including deaths over time.

Later, Project Sundial would push this logic into pure apocalypse. A true doomsday device, Sundial was designed to create a fireball 400 kilometres wide — enough to incinerate a continent and plunge the world into radioactive twilight. It was not a weapon of deterrence but of absolute erasure. Unlike the Nagasaki bomb, which destroyed a city, Sundial was engineered to destroy the idea of cities altogether. See this clever animation by Kurzgesagt.

What Nietzsche called the “Will to Power” — so often romanticised as creativity or self-overcoming — has its inverse in the will to destroy that which cannot be dominated. Power, when frustrated, becomes spite. And when spite is mechanised, the result is Nagasaki.

If, as Nietzsche warned, “when you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you,” then Nagasaki was the abyss returning the stare — with light, heat, and gamma rays.

But perhaps the most dangerous drive is not domination, but consolation.

That is, the human need to believe that someone — or something — is in control. In The Future of an Illusion, Freud observes: “Religion is an illusion and it derives its strength from the fact that it falls in with our instinctual desires.”

The atomic bomb, too, is a kind of religion — one baptised not in water, but in fire.

It offers the illusion of control over death by promising death on our terms. In place of gods, we built machines. In place of prayer, launch codes. These are our new delusions, our new opiates — the belief that technology will save us from the very death drive it mechanises.

The legacy of Nagasaki, however, is not fixed in the past. It is embedded in the logic of AI and military autonomy that governs the present.

We now train machines on our own histories — our genocides, our drone wars, our penal colonies, our prejudices — and ask them to protect us.

Worse, we give them the right to kill. Autonomous weapon systems, trained on “data” extracted from centuries of colonial conquest and algorithmic policing, are being built not to avoid another Nagasaki, but to replicate its efficiency at scale.

The Frankenstein scenario is no longer the stuff of Mary Shelley’s gothic imagination; it is a Pentagon-funded line item, accelerated by DARPA (the US Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency) and validated by Palantir’s predictive policing systems.

An AI trained on human history is not a wise steward. It is a mirror. And what it sees is slaughter.

Ellsberg spent the last years of his life warning us that the nuclear machine he once helped build had never been dismantled — only updated.

The so-called Doomsday Machine still exists, and both Russia and the US own one. They are wired with automated retaliation protocols that could trigger extinction through miscalculation or malfunction. AI does not solve that problem. It deepens it.

In his final, despairing book Mind at the End of Its Tether (1945), HG Wells wrote that humanity had likely reached the limits of its mental evolution, and that new modes of being would need to arise — or we would perish. That same year, the United States dropped two atomic bombs on cities full of civilians, and firebombed another.

Nagasaki wasn’t the end of the war. It was the beginning of a new kind of uncertainty — one that only gets more dangerous with each advance in artificial cognition and each reduction in human oversight.

As we drift toward new cold wars — with China, Russia, even ourselves — the Nagasaki anniversary should serve not as a historical footnote but as a moral alarm.

We dropped two bombs. One wasn’t enough.

The real lesson of Nagasaki is not how we won a war, but how close we came to ending the world.

Let us not build smarter bombs or better “defensive” AI. Let us, instead, get smarter than our own instincts.