fingers

fingers

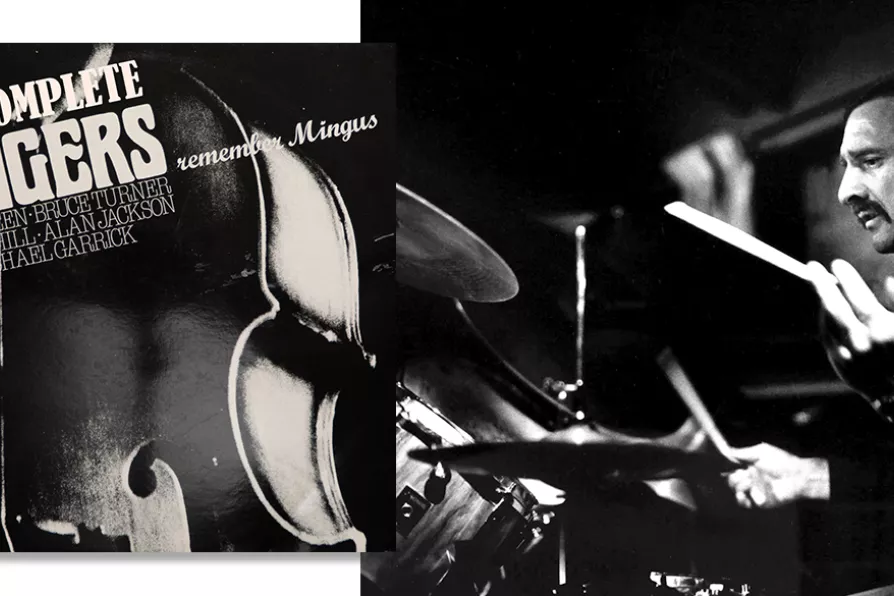

FINGERS was a quintet with a powerful personnel, a revolutionary jazz intention and a sound which was a surprising and riveting amalgam of heterogeneous styles and traditions.

When they recorded their limited edition album in 1979, they created a timbre previously unknown in British jazz. Pianist Michael Garrick, bassist Dave Green and drummer Alan Jackson were a regular trio, but Fingers’ two horn players were musical eccentrics who between them, could play just about anything.

Clarinettist and alto saxophonist Bruce Turner had played in the Dixieland band of Freddy Randall and been tutored in New York by arch-modernist Lee Konitz. When he joined the Humphrey Lyttelton Band in 1953, despite being caricatured as a “Dirty Bopper” by the jazz tribalists of the era, he adapted to Humph’s Kansas City style, playing empathetically alongside visiting US Basie-ites like trumpeter Buck Clayton and tenorist Buddy Tate, as well as forming his own jump band. He wrote regularly on jazz for the Daily Worker, the Morning Star’s predecessor, and accompanied folk singers Ewan McColl and Peggy Seeger.