The Visionaries: Arendt, Beauvoir, Rand, Weil and the Salvation of Philosophy

Wolfram Eilenberger, Allen Lane, £25

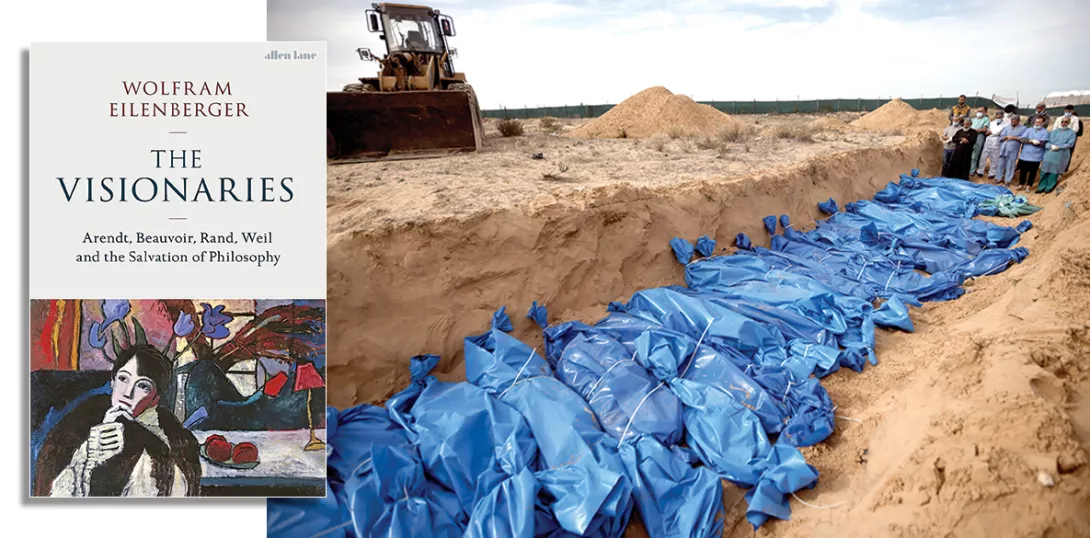

COMING in this time of war The Visionaries offers insights into the human capacity to think through violence.

Remarkable women caught up in the second world war totalitarian machine: Hannah Arendt and Simone Weil are Jewish women fleeing the Gestapo; French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir is trapped in Vichy France. These women’s experiences are captured in this group biography along with radical ideas that shaped a century, born from painful comprehension of human atrocity.

And somehow (bestseller) Ayn Rand gets in the mix; a Russian-Jewish refugee from Stalinism, her writing is shamefully exposed for its inadequacy when read next to the others.

Taking in the period from 1933 to 1945, German writer Wolfram Eilenberger maps the women’s escape routes: from Leningrad to New York, Berlin to Paris, from civil war Spain to France under occupation, major figures of contemporary thought are seen through the separate struggles to survive when all rules of justice and society are off.

Out of their experiences powerful philosophies grow. Eilenberger gathers together their discoveries to show, in parallel, the dynamic of intense creativity through world war. A major strength of the book lies in the connections made between developing trains of thought: no matter the difficulties the women never stop pushing forwards new conceptions of subjectivity – what it is to be a thinking consciousness in relation to others.

The Visionaries achieves, in part, a difficult feat, drawing out essential links between lives lived through turmoil, and experience abstracted into metaphysical terms. The outcome overall is a sense of great minds at work. Giant sources of modern philosophy – Kant, Heidegger, Hegel – filter into the discussions.

A weakness lies in the summary nature of the book – four huge personalities condensed into a modest-sized volume (much interleaved with blank or quarter pages) inevitably reduces the work to a skim of surface information, rather than vivid representation.

The book opens with Simone de Beauvoir in Paris at the Cafe de Flore. She is grappling with the eternal conundrum for philosophy – the relation of the finite existence of the “I” to the infinite abyss of non-existence. In one sense, de Beauvoir acts as a foil for the existential dangers faced by Arendt and Weil.

She is shown warts and all in predatory joint enterprise with a cosseted Jean Paul Sartre, acting out a modernist version of Liaisons Dangereuses with their teenage students. War intervenes to imprison Sartre, mandating Beauvoir to unleash her own intellectual genius, independent of her “little one,” as she calls him.

What she develops is a more subtle philosophical take on existentialism to Sartre’s, one in which the achievement of freedom for the Other is integral to the freedom of the individual.

A relief from the petit bourgeois Beauvoir, Simone Weil emerges as the true “visionary” of the book. Her commitment to a philosophical life is out of any time or place. An unworldly idiot savant, her complex of contradictions is extravagant. Partisan gun-toter in Spain, but nearly blind. Devoted to solving world hunger, but suicidal anorexic. Spiritual leveller of her own ego to the point of death, but petulant bully of her parents.

A Jesus/Joan of Arc dressed in the uniform of the International Brigades, Weil is both touchingly human in her flaws and yet extraordinarily luminous in her thinking. Camus called her “the only great spirit of our times.” De Gaulle said she was insane. Flannery O’Connor thought her “a mystery that should keep us all humble.” Trotsky rowed with her but claimed “We have founded the 4th International in your apartment.”

Weil’s philosophy is one of attention to, or immersion in the suffering of others, as the means of identification with the human predicament: our vulnerability to death. The excerpts from her writing resound through current events.

In direct relation to the immediate horror in Gaza, Hannah Arendt’s clear thinking foresaw the problems in exact dimensions. She was furious at the zionist movement’s 1942 resolutions to model an ethnically homogeneous Jewish nation-state in Israel, “with the actual Arab majority population given only minority rights (not including the right to vote)”.

“Nationalism is bad enough when it trusts in nothing but the rude force of a nation. A nationalism that necessarily and admittedly depends upon the force of a foreign nation is certainly worse,” she wrote.

In the rear-view mirror of Arendt’s refugee escape her friend Walter Benjamin is glimpsed shortly before his death. His famous Angel of History is turned towards the past. What we perceive as a chain of events Benjamin describes as a single catastrophic storm, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage skywards: “The storm is what we call progress.”

Reading this book as the debris in Gaza mounts along with the death toll, the obligation to attend, to think and keep thinking through hideous times, is the message from these women’s achievements.