THE Christmas season has a special connection to miners for me. It all began years ago when I first read Charles Dickens’s classic, A Christmas Carol, and noticed the poignant place mineworkers have in the story.

And I was very pleased to discover that the National Coal Mining Museum has given prominence to this on their website with a page devoted to Voices in the Coalshed, a volunteer project exploring “the language and literature inspired by coalmining.”

“At one point,” they explain, “the Ghost of Christmas Present takes Scrooge to “a bleak and desert moor where monstrous masses of rude stone were cast about as though it were the burial place of giants.” A horrified Scrooge is told that this is, “a place where miners live, who labour in the bowels of the earth.”

Dickens then reminds us, as Scrooge is transported to a humble cottage where four generations of miners are singing together, how love and family bonds are in abundance where wealth is not. It’s a crucial episode in the miser’s transformative journey and is always a special moment for me in the book because I was born into a family of miners in the Welsh Valleys and my grandfather’s birthday falls in the Christmas season.

His name was Iestyn Davies, and he first went down a mine when he was 14 years old. It was the Gorky drift mine owned by Cambrian and no place for a child. The conditions my grandfather worked in were highly dangerous, as evidenced by a disaster at his mine which might have claimed him had he not, by pure chance, been on a different shift that day.

Seven men were killed and 53 injured when a trolley carrying them to the works below sped out of control after the brakeman above suffered a blackout. Most of the deaths and injuries were caused by men jumping from the trolley only to be thrown back under it by the narrow walls of the shaft.

It is a strange and sobering thought that if fate had assigned my grandfather another shift, my mother might never have been born and I would not be here now writing this article.

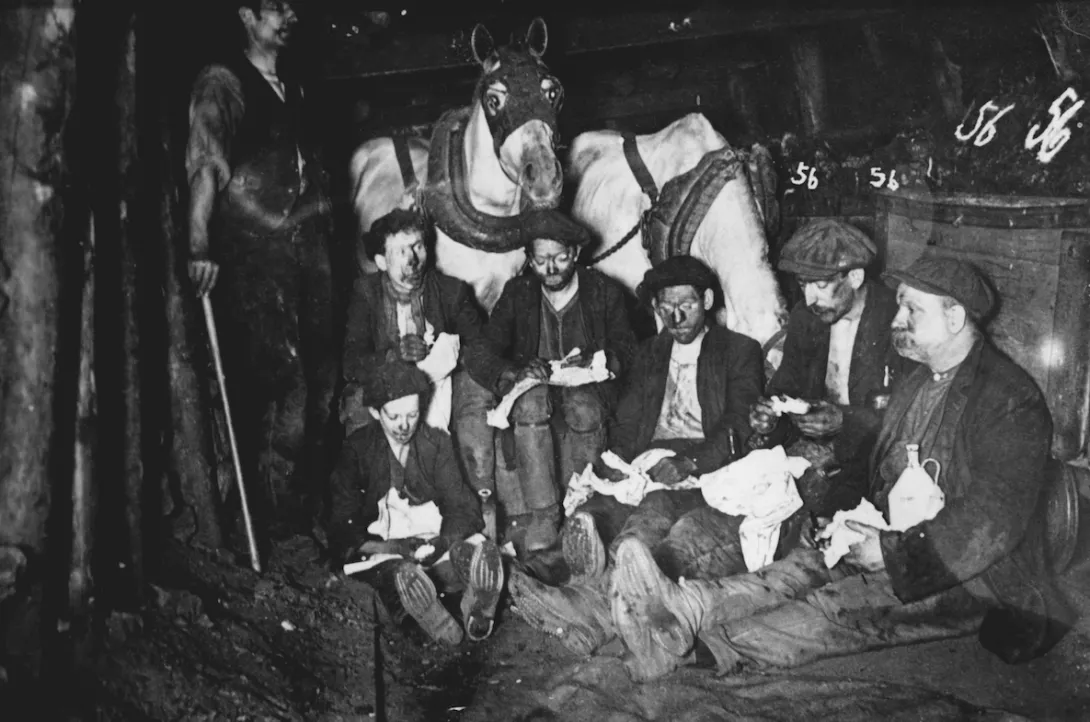

My mum remembers her father “working in what he called the 4ft.” All I knew was that he had been a coalface worker, cutting the stuff right out of the seam while on his knees; this sounded awful enough, but it wasn’t until I read George Orwell’s first-hand account of going underground with miners in the 1930s in his book The Road to Wigan Pier that I finally had it brought home to me the conditions he endured: “The first impression of all, overmastering everything else for a while, is the frightful, deafening din from the conveyor belt which carries the coal away. You cannot see very far, because the fog of coal dust throws back the beam of your lamp, but you can see on either side of you the line of half-naked kneeling men, one to every four or five yards, driving their shovels under the fallen coal and flinging it swiftly over their left shoulders. They are feeding it onto the conveyor belt…”

All miners share the accolade of a spirit and courage to which the litany of their untimely deaths is a testament. There is bravery inherent in going underground and dignity and virtue in doing the back-breaking labour that carries such risks.

The miners, too, who have suffered and died of illnesses caused by their years of toil have not gone unremembered. These many victims of sudden death or slow decline all belong to a distinguished and singular class of men. The very least they deserve are safe working conditions and decent pay, things they have had to fight for tooth and nail against those who value profit above human life and human dignity.

One of the most significant of these struggles was in 1910 when a cartel of mine owners, the Cambrian Combine, setting all conditions and pay, posted lockout notices after Rhondda miners refused to accept the withdrawal of allowances that made up their wages if they worked a difficult seam of coal.

Wages were linked to the amount of coal produced so a troublesome seam meant a significant drop in the already low amount paid. When the men went out on strike, thousands from other pits did the same in solidarity, leaving only one functioning pit at Llwynypia.

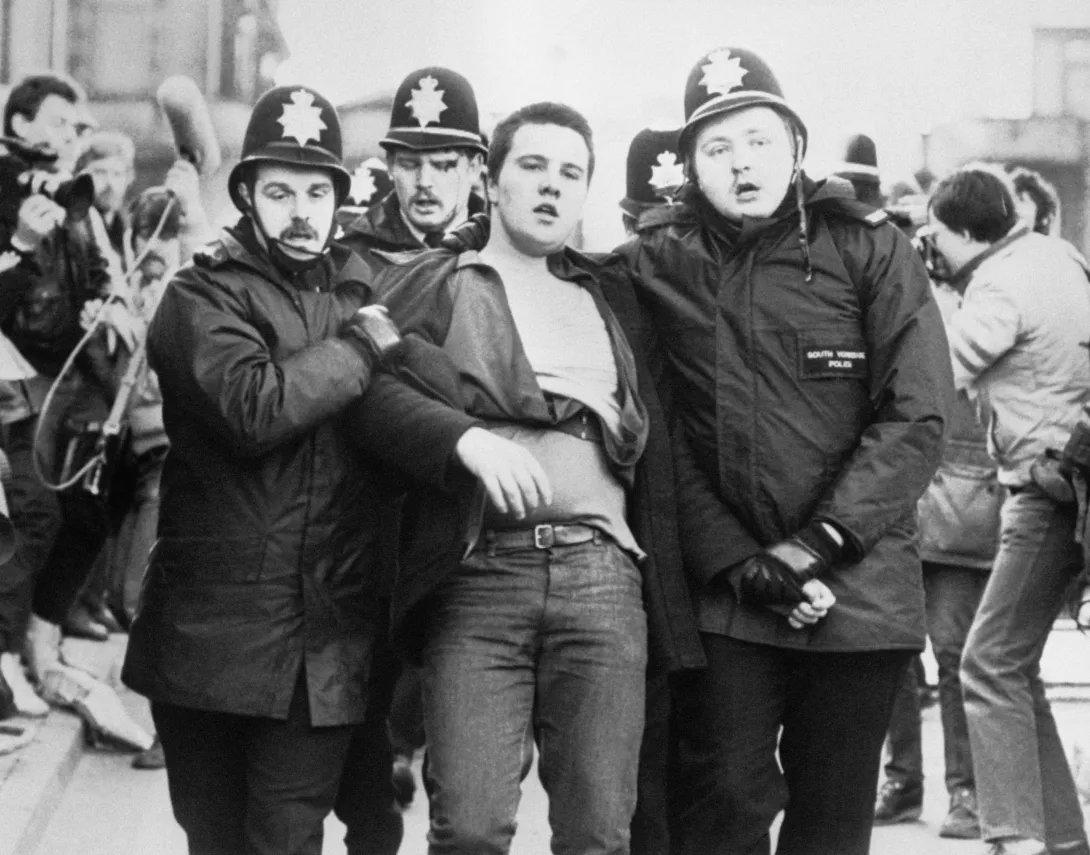

Tensions rose dramatically after the Cambrian Combine tried to bring in strike-breakers here and in the unrest that followed pitched battles were fought with police. Later, colliery officials’ houses and shops were targeted and a miner, Sam Rhys, died after being hit with a police baton. Winston Churchill gave the green light for General Macready to send in the military, a move which ensured that Churchill’s name is despised in Wales to this very day.

It is reported that miners and their wives fought with troops wielding rifles with fixed bayonets, but the worst violence was seen on one day now known as the Tonypandy Riot when 80 police and over 500 others were injured.

Jail sentences imposed on some miners were followed by a 10,000-strong march in protest, but in the end, hunger won. The men returned to work after a year on a pittance wage of £2.1s.2d.

Twenty-four years later, the Gresford mine disaster of 1934, in which 266 men were killed in an explosion at the Gresford Colliery, Wrexham, gave us Gresford: The Miner’s Hymn:

“They spend their lives in dark, with danger fraught,

Remote from nature’s beauties, far below

Winning the coal, oft dearly bought

To drive the wheel, the hearth make glow.”

This tragedy was followed by a historic inquiry which paved the way for post-war nationalisation of the industry. Cyril Jones, a partner in the law firm that represented the miners, believed, according to his grandson, that “what happened that day was one of the best arguments in favour of nationalisation and taking the mines out of the hands of private coal owners.”

But mining disasters are not a thing of the past; in 2011 the deaths of four miners at the Gleision Colliery in the Swansea Valley were a tragic reminder that even in our high-speed, high-tech society it is still possible for men to lose their lives doing this dangerous work. A friend of the family of lost Gleision miner, David Powell, said: “The pit was constantly filling with water — it was a constant battle to keep it pumped out so the men could go down there.”

My cousin worked at Gleision for only a few days because it was “so dangerous” that he refused to return. Safe working conditions for miners are not an issue that belongs to a bygone era, but one that requires continual vigilance. How otherwise can we call ourselves a civilised society? A tribute left at the Gleision mine read: “The day’s work is done, your tools are on the bar. No more sweat and no more pain. Rest in peace.”

Miners the world over are, disgracefully, still suffering in unsafe working conditions; on December 2 this year 11 miners were killed and 75 others injured at an Impala platinum mine in South Africa when an industrial elevator hoisting employees to the surface suddenly plummeted. And in February two miners were missing 125m underground after a collapse at a Queensland mine. Only days ago it was reported that the miners trapped underground in India had all been rescued, thank God.

All of these brave souls are now apostles of empathy for all the victims of mining that have gone before them, and for all miners still quarrying, wherever they are. I’m sure Charles Dickens would join us in saying: here’s to them! And here’s to my grandfather, Iestyn Davies, “Dad.” I can’t think of a finer dedication to him — and them — than the one that hung for years on the wall of Llanhilleth Workmen’s Institute:

A Welshman stood at the Golden Gate his head bowed low

He meekly asked the man of fate the way he should go

“What have you done?” St Peter said “To gain admission here?’

“I merely mined for coal,” he said, “for many a year”

St Peter opened wide the gate and softly tolled the bell

“Come and choose your harp” he said “You’ve had your share of hell.”