Barbara Walker

Towner Eastbourne

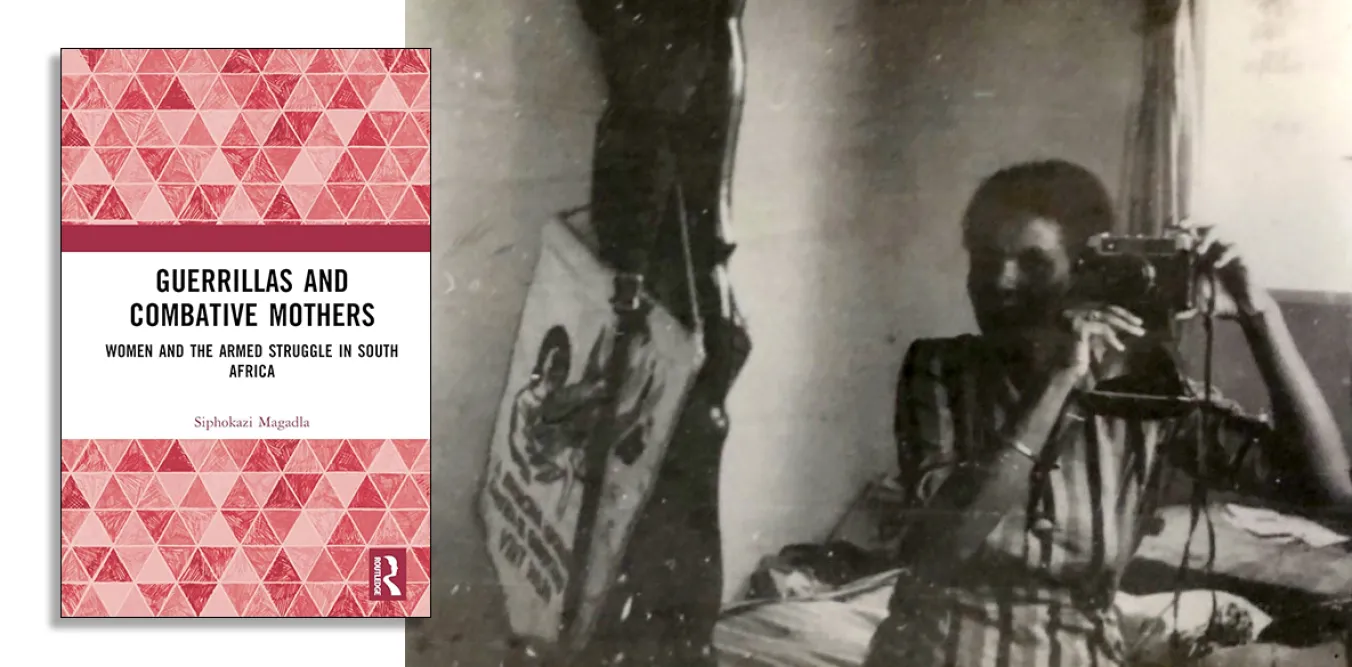

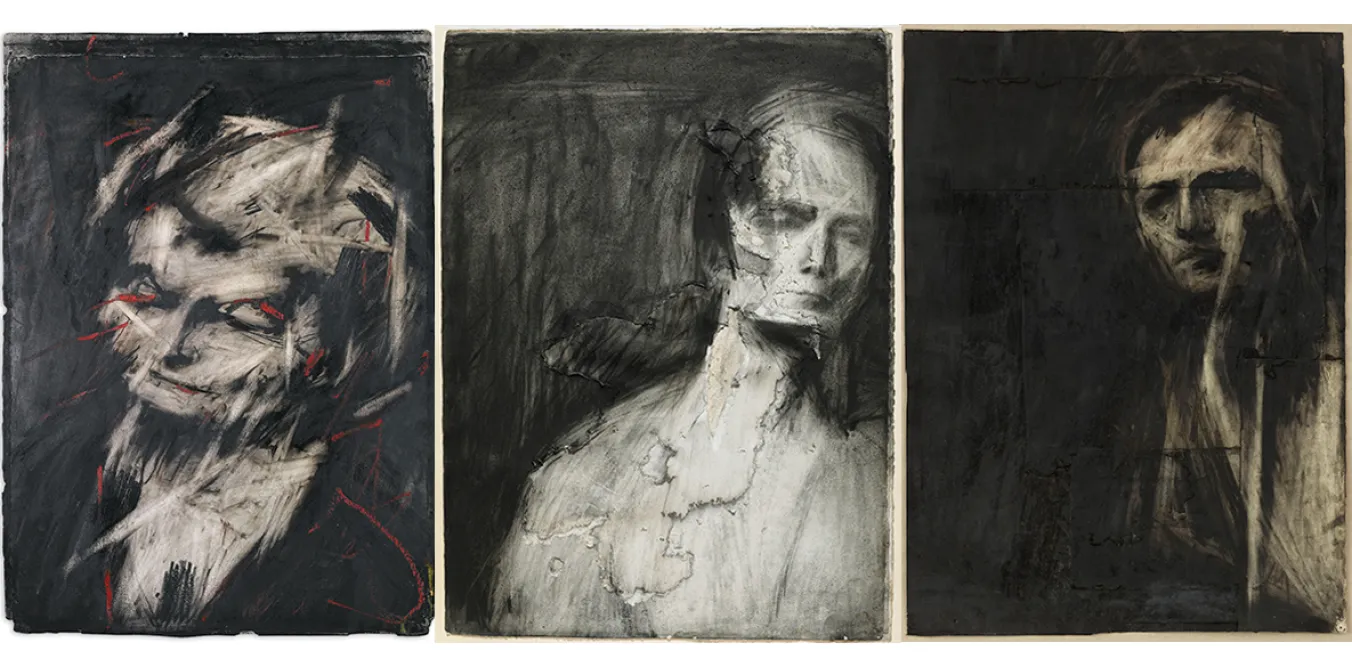

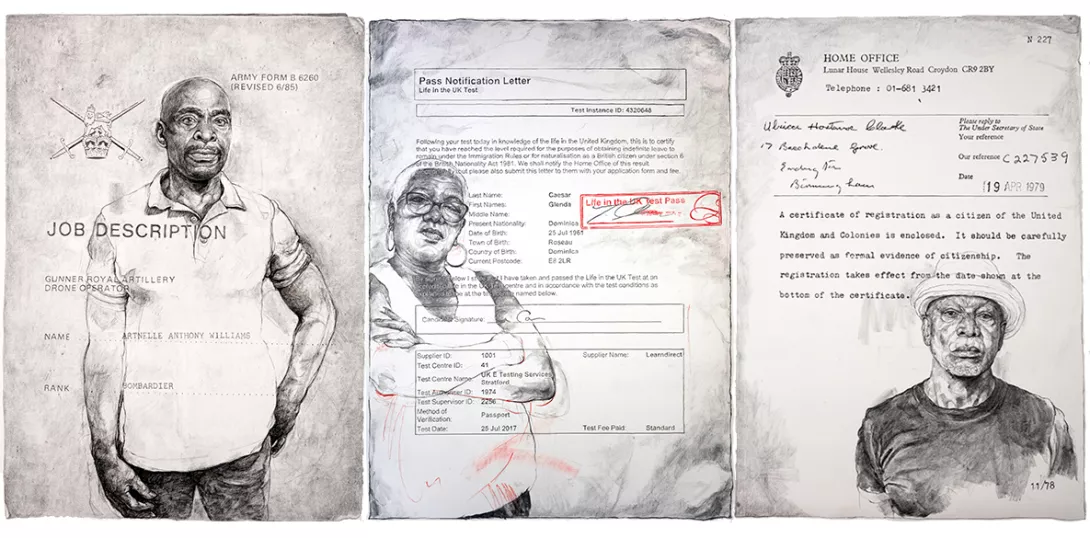

THE image of Glenda Caesar stares out from the corner of Burden of Proof 10. Arms folded, head tilted defiantly; a strong, independent black woman, daring you to question her. Her arms are roughly sketched, laced with flecks of red that seem to come from the official stamp across the work. This is the Individual against the State.

Barbara Walker works in a range of media and formats, from embossed works on paper to paintings on canvas and large-scale charcoal wall drawings. The work from her exhibition Burden of Proof put her in the running for the Turner Prize, and can be viewed for free at the Towner Eastbourne.

“Burden of Proof surfaced in 2018,” says Walker “when it emerged that high 100s of Caribbean citizens who particularly came from the Windrush generation were denied legal status, deported and basically categorised as illegal immigrants. I was quite angry. I was quite upset. And I immediately thought of my mother and father: would they be subjected to this?

“And to think that these citizens were invited to Britain to help support the country after WWII, and then to be categorised as illegal immigrants — it’s heart-wrenching! It’s very callous, it’s very sad. I need to make work about it. I need to respond to it.”

Frantz Fanon said: “The end of race prejudice begins with a sudden incomprehension,” but Walker puts it another way: “I realise why these individuals were a bit apprehensive in coming forward. A lot of them were tired, ground down, either from waiting for the result of an application, or from the shame …

“We are often told not to talk about our business or to share our private business in public … which is another erasure! That quietness, it’s a quiet erasure happening behind the scenes.”

This is reflected painfully in her work, as “applicationforms” represent the paper trail these individuals have had to go through, as her line drawings turn into people who have been excluded by the capitalist bureaucracy: “There’s a tension in the documents — the overlapping of figure and drawing is deliberate — almost as though the document is more important than these individuals.

“So, with that in mind I asked participants to give me two documents. That would be the backdrop. And then there’s the overlapping of their portraits and the documents. That’s provocative in many ways because they’re telling a story. It also reveals that these individuals have contributed to this country. If that’s a piece of paper, these are real people, these are real lives …”

Growing up in Birmingham, Walker’s experiences have shaped a practice concerned with issues of class and power, gender, race, representation and belonging. In the show Louder Than Words she drew images of her own son over “dockets from the police,” where large areas of white appear erasing the police report. For Walker it’s “trying to erase the experience, the feeling. I’ve always been erasing my work! Consciously, or subconsciously it’s always been a key signature in my practise: how to represent erasure, and exclusion.

Then she translates the drawing to the wall in order for these presences to inhabit the space: “So you can hear their voices through the work, and also their expression, and the concept … it’s looking at individuals directly affected by the scandal, and also those connected to the participants, partners, children … there’s a ripple effect, a generational ripple effect that’s ongoing.”

It’s a seizure of power, but it’s also paradoxical: “All the time I create these drawings I know they’re temporary, so in a way I’m already saying goodbye when I begin the first mark.”

But, for sure, the installations amplify the message, and recruit drawing as a medium for activism, to make a “huge statement” in spaces “that can be very intimidating.”

And also, she says: “It’s about me — the visibility of me. The message is taking the anonymous, the powerless subject. Usually an individual, or the black subject. I’m very interested in the body politics — identity belonging and power — how power manifests itself in society who who owns the power. I subvert that narrative and take those who are excluded, bringing them into a space, bringing them to the surface, giving them back the power, giving them permission to tell their stories.

“What I do hope is that people can see, engage, read the work and from it somehow we can contribute to making something better …”

Her work reminds me of the James Baldwin quote: “If one really wishes to know how justice is administered in a country, one does not question the policeman, the lawyers, the judges, or the protected members of the middle class. One goes to the unprotected — those, precisely, who need the law’s protection most! — and listens to their testimony.”

Runs until April 14 2024, admission free. For more information see: townereastbourne.org.uk