Looking at Picasso

Pepe Karmel, Thames and Hudson, £45

If any Western modernist has a secure reputation, it has to be Pablo Picasso, thanks to his variety of art, very long working life, and celebration by generations of critics. Pepe Karmel’s Looking at Picasso starts with a statement that is sure to be highly controversial: “Picasso was the greatest artist of the twentieth century.”

But could that judgement change?

When the last volume of John Richardson’s biography was published in 2022, New York critic Siri Hustvedt wrote: “He is a signifier for male genius that caters to a collective sickness, which revels in the denigration and punishment of women. It is this broader cultural myth, founded on context-dependent prior beliefs, that requires interrogation, not by censorship, but by discussion, a discussion that is absent from Richardson’s biography.”

Many contemporary writers would agree with her claims.

Karmel’s book is a highly sophisticated, comprehensive and tightly edited life with excellent plates. It covers Picasso in a way that is both far reaching in exploration of the vast literature, and fair-minded, a combination which is not easy to achieve. The successive chapters cover his early works, cubism and then to return to more conservative images, surrealism, Guernica and Picasso’s political art, and a little (too little maybe) on the late art. Looking at Picasso is an amazing scholarly achievement.

What’s at stake here are not the facts, for Picasso’s life has by now been very well documented. Rather the question is what to make of these facts.

Everyone is agreed that Picasso, born in 1881, was a man of his time, wildly promiscuous, often overbearing, and sadistic in his treatment of women. His art reflects his personality. But also, as Karmel notes, he was often tender, sometimes brave and frequently generous to many friends. And many women and men find his art immensely affecting.

What’s special about the case of Picasso is that because he was so famous, rich and powerful, he could act on a scene typically found only in the lives of Dotcom billionaires or celebrities from the entertainment industry. The long-standing pattern of his exploitative relationships, as a very prosperous older man, with young attractive women, is something that now attracts suspicion.

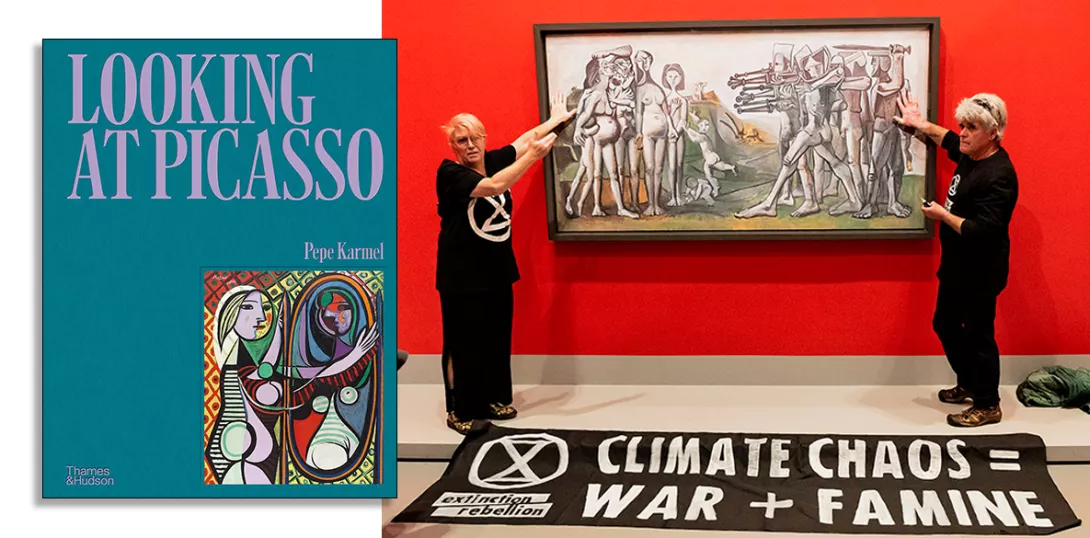

But what now heavily influences this discussion are very legitimate worries about the overheated art market, the status of the art museum and the whole history of colonialism, MeToo and present political protest movements. And if Picasso is an ideal stalking horse for this critical thinking, that’s because he is so prominent a white male European artist.

Thinking with real uncertainty about how to plausibly present these concerns, I focused on Karmel’s book and asked myself whether Siri Hustvedt’s critique is plausible. I contemplated the many plates to find relevant examples.

Karmel discusses Meditation: Contemplation (1904), in which the watcher attends to his sleeping female companion. He analyses The Painter and His Model (1927), Picasso’s image of a man performing oral sex on the woman. And he presents the artist’s portrait of his son Paolo on a Donkey (1923). In general, neither the cubist works nor the still lives nor the many late remaking of old master pictures are likely to bother Picasso’s critics. It’s surrealism that mostly causes the troubles, for there Picasso’s sadism holds reign.

But in developing this analysis, I don’t mean to hold my evaluation of Karmel’s book hostage to these larger cultural changes, whose outcome is by no means clear. Looking at Picasso stands on its own and as a model of how to do politically responsible art history, it is as good as it gets.

Kernel says that his book, neither a biography nor an account of Picasso’s vast influence, celebrates the artist’s freedom. He achieves that aim with entire success. Picasso the cubist, the neo-classical artist and the political painter: all of these very varied figures appear in clear focus. In the future, will that freedom be more generally shared? While the question is as yet impossible to answer, Looking at Picasso is an essential contribution to this ongoing discussion.

This is an abridged version of an article that first appeared in Counterpunch